A Patient’s Life Depends on Product Quality What is Truly at Risk When We Look at Alternative Endotoxin Testing Solutions?

There will always be scientific debate when current testing solutions are replaced with innovative alternatives. This discourse is crucial as it inevitably leads to mutual understanding among leading experts. When there is a consensus with respect to empirical data, industry and regulators should move unanimously to accept a new technology.

The benefit of achieving a collaborative consensus is that more informed decisions can be made due to better understanding of the potential risks of these process changes. Manufacturing controls, release testing, and, ultimately, patient safety, are directly affected when implementing unregulated test reagents.

Patient safety must endure as the primary consideration for all medical and consumer products distributed for human or animal use. Replacing or enhancing a safety test is easiest to justify when the current methodology is a subjective test method that presents known probability of false negatives, and/or when there is a need to advance to more rapid methods due to shorter shelf life products. In these cases, expediting the implementation of new, data-substantiated and highly sensitive and objective methods is understandably warranted. The primary example of a safety test that may no longer be the ideal option for many products is the compendial sterility test, USP <71> Sterility Test.

While this century-old “gold standard” of safety testing has, and continues, to serve the public well, it is nevertheless a lengthy and subjective test that has been rightly challenged over the past few decades as alternative methodologies have demonstrated verifiable advantages with respect to parameters such as speed, sensitivity, specificity and objectivity. Yet even in the case of alternative sterility tests, data-based evidence is required to support that the new methodology is “equivalent or better” than the compendial standard. It remains the responsibility of industry and regulators to validate and approve all changes to safety testing methodologies. Those who have worked to validate an alternative sterility test know all too well how difficult it is to ensure that the risk of false negatives does not exceed the current risks introduced by the use of USP <71>. Regulators challenge the data in these submissions to ensure the new method can detect the myriad of organisms that exist in the environment under various stresses and at low inoculums. The data must also be repeatable and statistically significant.

This same threshold is applied to the bacterial endotoxin test using Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL). Here, years of parallel LAL and rabbit pyrogen testing were required to ensure safety and efficacy. The volume of data and the number of independent studies were all necessary along with the fierce public exchange of ideas. An LAL test has never resulted in harming patients due to a confirmed false negative result.

rFC Unproven?

With this history, why are companies not expected to perform the same extent of equivalency testing, ensure safety and efficacy, and produce data for comparison to prove recombinant factor C (rFC) is equivalent or better than LAL?

Not only is current data on rFC limited in comparison to what is needed to gain approval for an alternate sterility test, it pales in comparison to the comprehensive and statistically meaningful data needed prior to the U.S. FDA’s acceptance of LAL as an alternative to the rabbit pyrogen test. We must not make assumptions with rFC when compared to the long history of LAL based safety testing and unparalleled specificity.

Equivalency must be proven, not merely portrayed as a speculated conclusion. For instance, it might be persuasive to read claims that rFC is a cloned equivalent zymogen produced from the same natural gene sequence from the horseshoe crab.

This claim, however, cannot conclude that the LAL and rFC are equivalent with respect to specificity of pyrogenic substances. This simplistic assumption overlooks the numerous variables that exist with rFC sourcing and production that must first be fully understood.

For instance, what horseshoe crab is referenced in this portrayal? Is it Tachypleus, Carcinoscorpius or Limulus? Now, while there is a large degree of homology between the species, there are differences nonetheless (1).

More importantly, is there consideration of the cell lines used to create genetically engineered Factor C? Recombinant proteins, even with the same amino acid sequences, are known to exhibit different post-translational modifications; specifically, different cell lines will create different glycosylation patterns. Other research has shown that rFC from Chinese hamster ovary cells are less susceptible to interferences than rFC from insect Sf9 cell lines (2). Not all rFCs are the same.

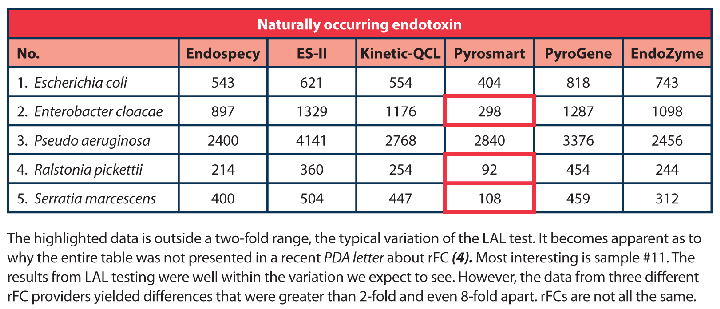

Some recently published articles pertaining to rFC demonstrate data and comparison studies with selected data and partial information from original source tables—incorrectly indicating that LAL underpredicts for several organisms compared to rFC. Results will never be identical for a sensitive and quantitative assay. These differences are comparable and well within the two-fold variation expected. Table 1 is the full dataset where this partial information was gathered (3). Having the full disclosed information provides needed confirmation that both LAL and rFC methods demonstrate results within the expected variation of the assay for the selected organisms.

It can be clearly seen in this data that the rFC methods underestimate endotoxin from a number of naturally contaminated water samples. It has been noted in a recent PDA Letter article that this difference is due to glucan contamination in the water samples (4); however, seeing that two of the three LAL reagents used were endotoxin-specific formulations, Endospecy and ES-II, and therefore do not react to glucans (12, 13), glucan can be 100% ruled out as having an influence on these results. This data demonstrates that there may be specificity issues to certain endotoxins when utilizing rFC.

In this same PDA Letter article, it is stated that there is a commitment to providing an “accurate portrayal of the emerging LAL replacement reagent rFC,” which follows with inaccuracies or misleading conclusions surrounding the available data (4). First, if the intent is to replace a safety test, the case ought not to be “a portrayal” at all but rather a process that results in mutual understanding and agreement within the scientific community. Expansive, empirical and indisputable data was required to establish LAL testing as an alternative to the rabbit pyrogen testing.

Data-based questions and commentary are essential when evaluating new technologies. It is also important to be transparent with all the data and not limited only to what fits a certain narrative. As can be seen in the complete data shown in Table 1 above, it is not necessary to further illustrate what was misleading. In fact, it does little good to insinuate such things. Industry only needs to see the data and where it certainly makes sense to coordinate additional studies to ensure patients remain protected from endotoxins.

Patient safety is a shared responsibility. The basic purpose of pharmacopeias, regulatory authorities, and manufacturers is to ensure that medicines and medical devices are safe and of good quality. Therefore, it will ultimately be the manufacturer’s responsibility for marketing unsafe products even when the risk was not known. Unexpected adverse events can and do occur even with the best designed and most controlled clinical trials.

In discussing rFC as an alternative to LAL, there is actually an identified risk with regard to specificity to naturally occurring endotoxins, as shown above in Table 1, or where a contamination is a mixed culture and undetected (5). If widely adopted, the likelihood that this will result in tragic, yet avoidable, patient health issues and events is of great concern and manufacturers will be held liable.

Elevating this concern is that rFC suppliers will not be subject to FDA premarket approval, since they will not need to report process changes to FDA as required for licensed LAL manufacturers. Plus, they will not be subject to routine inspections. The controls to ensure manufacturing quality and consistency for a reagent used to determine the safety of thousands of medicinal products will not have any regulatory oversight. This approach should be reevaluated as it opens the door to numerous global manufacturers of rFC, potentially resulting in uncontrolled variables with respect to recombinant source cells, manufacturing processes (including cell banking) and release testing. And drug manufacturers will remain liable for safety issues in the field related to their use of rFC, just as they were held liable for past transgressions, such as the notorious sulfanilamide and thalidomide tragedies. History has, and will, continue to judge regulators and those responsible for ensuring medicines are safe and of good quality.

Keeping patient safety a top priority ensures the industry remains on the right side of history. This means working closely with regulators, as when LAL was adopted as an alternate to rabbit pyrogen testing. Concerns regarding rFC and other recombinant LAL products can be alleviated by a global collaborative effort to conduct the studies needed to obtain statistically significant, microbiologically sound and undisputed data sets. Rapid adoption should not be interpreted as having more value than certainty of patient safety. The call for caution before adoption as exemplified by the efforts of Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey is history that should never be forgotten.

[Editor’s Note: This article is part of an ongoing dialogue on alternative endotoxin testing technologies.]

References

- Ding, J.L., and Ho, B., “Endotoxin detection--from Limulus amebocyte lysate to recombinant factor C.” Subcell Biochem 53 (2010): 187–208.

- Mizumura, H., et al. “Genetic engineering approach to develop next-generation reagents for endotoxin quantification.” Innate Immunity 23 (2017) 136–146.

- Kikuchi et al “Collaborative Study of bacterial Endotoxin Test using Recombinant Factor C based procedure for Detection of Lipopolysaccharide.” Pharm. and Med. Dev. Reg. Science 48 (2017) 252–260.

- Williams, K. “Response to ‘Standing Guard.’” PDA Letter (Feb. 2019) 17–19.

- Wassenaar, et al. “Lipopolysaccharides in Food, Food Supplements, and Probiotics: Should We be Worried?” Eur. J. of Microbiol. and Immunol 8(2018) 63–69.