An Overview of Container Closure Integrity Considerations for Achieving an Optimal Performance Window for Container Closure Systems

[Editor’s Note: This is based on the author’s presentation at the 2018 PDA Container Closure Performance and Integrity Conference.]

A typical container closure system has three major components: a rubber stopper, a vial and an aluminum seal. In order to satisfy mandatory patient safety requirements, container closure integrity must be ensured through a holistic consideration of many critical aspects (1).

The combination of compatible container closure system components, together with a proper capping process setup, is crucial to ensuring reliable container closure integrity performance—a fundamental requirement of every sterile drug package. Therefore, it is vital to have suitable container closure system components with reliable sealing properties to achieve long-lasting container closure integrity performance throughout the entire product lifespan. Here, lifespan refers to the time interval from the moment the vial assembly is capped until the drug is administered to the patient.

Fortunately, there is a way to achieve an optimal performance window by following the adage of “working smarter not harder.”

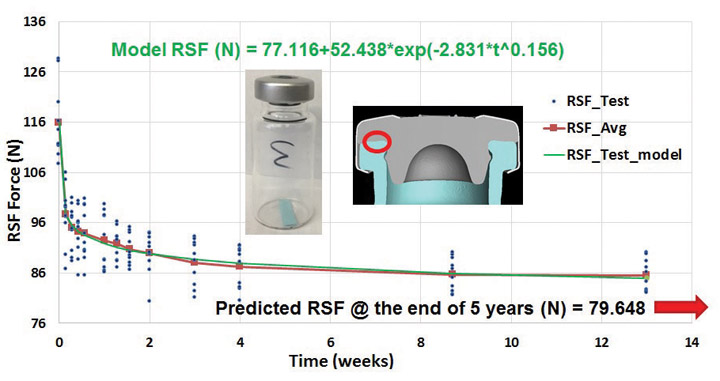

In order to ensure acceptable container closure integrity performance, a container closure system must maintain adequate residual seal force (RSF), the force that a rubber stopper flange exerts against the vial flange surface in an assembled, capped container closure system (2). The RSF within a container closure system is time-dependent, decaying exponentially over time and eventually leveling off due to rubber stopper compression stress relaxation, as shown in Figure 1 (3,4).

Typically, rubber stoppers are made of rubber compounds primarily composed of polymers and fillers. Rubber polymer molecular structures may be linear, branched, cross-linked or networked, all of which affect the chemical, physical and mechanical properties of the rubber stopper (5,6), resulting in both elastic and viscous resistance to compression (7,8). In effect, rubber stoppers can retain the recoverable (elastic) strain energy partially, but also dissipate energy (viscous) partially if compression is maintained. Therefore, under constant compression, rubber stoppers undergo stress decay, known as compression stress relaxation (7,8). The Maxwell-Wiechert model simulates rubber stress relaxation under compression (7,8). Figure 1 is an example from a case study showing RSF decay testing data and modeling predictions based on the Maxwell-Wiechert theory.

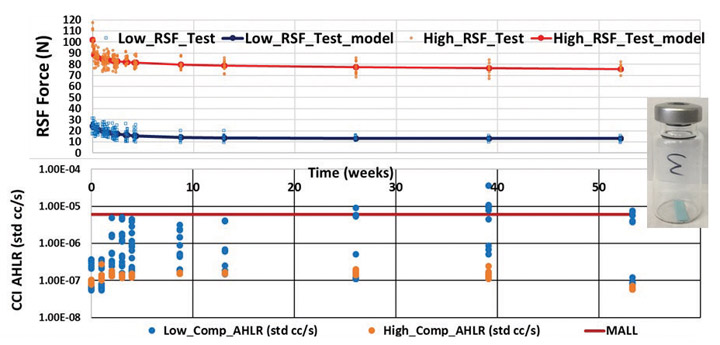

Since the RSF relaxes over time due to the viscoelastic characteristic nature of the rubber stopper materials, the magnitude and rate of RSF decay depend on rubber polymer molecular structure, rubber formulation, rubber properties, container closure system dimensions (stopper, vial, and aluminum seal) and capping process setup (4). In fact, RSF decay can be engineered, to a certain degree, through rubber molecule structure design and material property modification for optimal container closure integrity performance. The resultant stress relaxation has an impact on whether the container closure system can successfully maintain adequate container closure integrity throughout the entire sealed drug product lifespan. To ensure acceptable container closure integrity performance throughout the product lifespan, proper stopper compression must be imposed by the capping process for sufficient RSF beginning at time zero. Typically, a high compression percentage leads to high RSF. Figure 2 represents an example taken from a time-dependent case study with testing data up to one year showing the relationship between RSF and helium leak container closure integrity results (9–11). In general, high RSF leads to relatively low helium leak results with tight statistical spreads for good container closure integrity performance, while low RSF results are associated with poor container closure integrity performance, causing relatively high helium leak results and large statistical spreads, increasing the risk of failing the maximum allowable leakage limit (MALL).

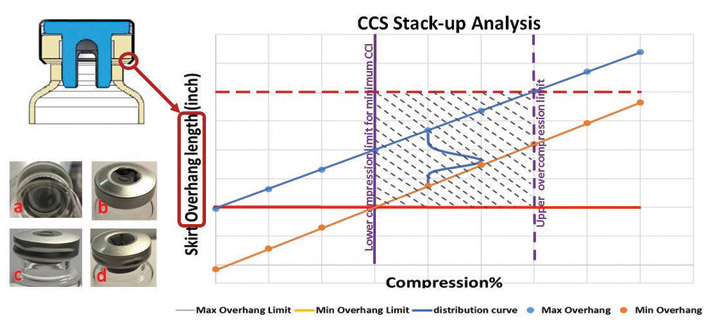

In general, a capping process must be set up with sufficiently high stopper compression to ensure that the RSF is high enough at time zero and throughout the entire sealed drug product lifespan to ensure container closure performance. Excessive stopper compression may cause cosmetic defects, however, adversely affecting visual appearance of a vial assembly. Figure 3 shows some photos of rejectable cosmetic defects due to excessive stopper compression during the capping process that resulted in visual inspection failure on a pharmaceutical manufacturing floor (9–11). These example defects include, but are not limited to, (a) seal skirt wrinkling under the vial flange, (b) stopper dimpling, (c) seal side buckling or (d) a combination of these defects—all because of excessive stopper compression during the capping process.

In light of all these conflicting challenges, it is imperative to strike a balance that satisfies all container closure system performance needs. In this situation, working “smart” means clearly defining and locating a balanced window to satisfy both RSF/container closure integrity performance with acceptable cosmetic visual appearance. As demonstrated in Figure 3, for mapping out a balanced container closure system performance window, the horizontal axis represents stopper flange compression percentage, and the vertical axis denotes seal skirt overhang length, defined as subtracting the summation of stopper flange thickness and vial flange thickness from the overall seal skirt length. Essentially, after completing the capping process at time zero, a vial assembly must have its container closure system stack-up dimension characteristics (located within the rectangular shadowed area in the chart on Figure 3) described as follows:

- Actual seal skirt overhang length will depend on stopper compression percentage, and it must be larger than, minimum overhang limit (horizontal red line) to properly assemble container closure system components together

- Actual seal skirt overhang length should be less than maximum overhang limit to avoid seal skirt wrinkling under the vial flange

- Actual stopper flange compression percentage must surpass lower compression limit to ensure sufficient RSF throughout the entire sealed-drug lifespan for acceptable minimum container closure integrity performance

- Stopper flange compression percentage should not be excessive and beyond the upper compression limit to avoid visual defects such as, but not limited to, seal skirt wrinkling under the vial flange, stopper dimpling, seal side buckling or any combination of these defects

In reality, stopper flange thickness, vial flange thickness and seal skirt length are statistical variables. As a result of container closure system stack-up, the seal skirt overhang length also becomes a statistic variable, in addition to its dependence on actual stopper flange compression percentage. The statistical distribution of overhang length is schematically represented as a green curve in the chart on Figure 3, and it moves along the track between the blue line and the yellow line depending on the actual compression percentage. The blue line represents maximum overhang length data points at discrete compression percentage points, and the yellow line corresponds to the minimum overhang length data points. The goal is to ensure the green distribution curve of overhang length is positioned within the rectangular shadowed area on the chart in Figure 3. This will lead to the satisfactory container closure system performance as described above.

In summary, working “smart” to ensure integrity of container closure systems requires focusing on compatible components with good rubber material properties, together with appropriate container closure system stack-up through proper compression percentage process setup to ensure optimal container closure system performance (RSF, container closure integrity and visual appearance) throughout the entire sealed drug lifespan. In fact, this container closure system compatibility for optimal performance window can be calculated, simulated, predicted, tested and assessed through an integrated system approach for critical data-driven risk management, provided sufficient container closure system component data is available.

References

- DeGrazio, F. Holistic considerations in optimizing a sterile product package to ensure container closure integrity. J. Pharma. Sci. Technol. 72, 15–34.

- USP <1207> Sterile Product Pack—Integrity Evaluation. In USP 41/NF 36. U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention: Rockville, MD, 2018.

- Zeng, Q., Zhao, C. Critical Time-Dependent Evaluation and Modeling of Rubber Stopper Seal Performance for Drug Product Life Cycle. Presented at the American Chemical Society, Rubber Division, 191st Technical Meeting, Beachwood, OH, April 25–27, 2017.

- Zeng, Q., Zhao, X. Time-Dependent Testing Evaluation and Modeling for Rubber Stopper Seal Performance. J. Pharma. Sci. Technol. 72, 134–148.

- Mark, J., Erman, B. Science and Technology of Rubber. 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, 2011.

- Boyd, R.H., Philips, P. J. The Science of Polymer Molecules. Cambridge University Press: New York, 1996.

- Ferry, J.D. Viscoelastic Properties of Polymers. 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1980.

- Ward, I.M., Sweeney, J. An Introduction to the Mechanical Properties of Solid Polymers. 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 2004.

- Zeng, Q. Critical Time- & Temperature Dependent Container Closure Integrity (CCI) Through the Sealed Drug Product Life Cycle. Presented at PDA Parenteral Packaging, Rome, Italy, February 27–28, 2018.

- Zeng, Q., et al. Data-driven Control Strategy for Critical Drug Container Closure Systems (CCS) Performance at Digital Age. Presented at INTERPHEX Technical Conference, New York City, April 17–19, 2018.

- Richard, C., Zeng, Q. Mechanistic Understanding of Container Closure Sealing Performance via Modeling and 4D X-Ray Computed Tomography. Presented at the 2018 PDA Container Closure Performance and Integrity Conference, Bethesda, MD, June 13-14, 2018.

[Editor’s Note: The author’s company is one of the sponsors of the PDA Parenteral Packaging conference.]