Challenges in Sterilizing Indirect Product-Contact Surfaces The Stopper Bowl Dilemma

For aseptic processes, EudraLex GMP Annex 1: Manufacture of Sterile Medicinal Products, requires that direct and indirect contact parts are sterilized.

Based on the current historical design of some filling lines, however, certain stopper bowls are either fixed, built-in or extremely heavy and not possible to remove for offline cleaning and sterilization. Facilitating the removal of these stopper bowls would require a significant redesign of existing lines. Therefore, a risk-based approach is needed to understand the risk of contamination during the preparation of the stopper bowl for aseptic production. Appropriate measures and controls should be developed and included in the company contamination control strategy document. This article proposes a risk assessment of two scenarios for the preparation of the stopper bowl—when it can be dismantled and when it cannot be dismantled. This article focuses on recommended procedures based on risk assessment and measures to mitigate the risk of contamination during aseptic production in both scenarios.

Background

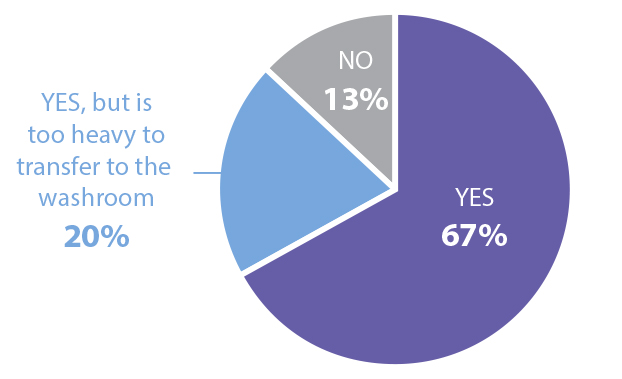

According to a survey conducted in 2023 to more than 65 companies from around the world, 67% have a detachable stopper bowl, while the remaining 33% have a stopper bowl that is either not detachable or too heavy to be dismantled for cleaning and sterilization. Of these companies, 28% are located in the United States and Canada, 11% in Latin America (Brazil and Mexico), 8% in Asia (India, Korea, and Indonesia), 3% in South Africa and 36% in Europe (Belgium, Germany, Spain, Switzerland, Netherlands, Denmark, Ireland, Italy, the United Kingdom and France) (1).

The survey shows that, as of 2023, there was a considerable percentage (33%) of manufacturers that do not comply with the requirements of the EU GMP Annex 1 2022 updates. For any newly installed filling lines, the expectation is clear that all direct and indirect product-contact parts should be able to be removed to be cleaned and sterilized offline. On the other hand, the implementation of alternative procedures differing from the recommendation in EU GMP Annex 1 will need to be justified with the tools of quality risk management (QRM) (2).

The analysis below utilizes the Failure Mode and Effect Analysis risk-assessment tool to identify and assess the different risks associated with detachable and nondetachable stopper-bowl scenarios. The goal of this exercise will be to see what the major challenges in both are and what would be the best recommendations in each case. Many assumptions are made along the way to assess both situations, such as a certain facility design or a positive pressure isolator as barrier technology, and manufacturers might arrive at a different conclusion depending on the design of their facilities, barrier technologies, controls and procedures in place. Further, the analysis will be done for the stopper bowl as a challenging item due to its size, but it is applicable to any other indirect surface in the filling line.

Before starting with the assessment of the two scenarios, a brief introduction to risk management methodology and the different scales defined to assess the severity, probability and detectability will be presented.

Risk Management Methodology

Risk assessments consist of the (3):

- Identification of hazards

- Analysis

- Evaluation of risks associated with exposure to those hazards

To identify the risk(s) within the lifecycle of a stopper bowl, three questions are asked:

- What might go wrong?

- What is the likelihood (probability) it will go wrong?

- What are the consequences (severity)?

The ability to detect the harm (detectability) was factored into the estimation of risk. The overall risk was quantitatively determined by multiplying the values of probability x severity x detectability for each identified risk. To quantify the overall risk, scales were defined to assess the severity, probability and detectability (3).

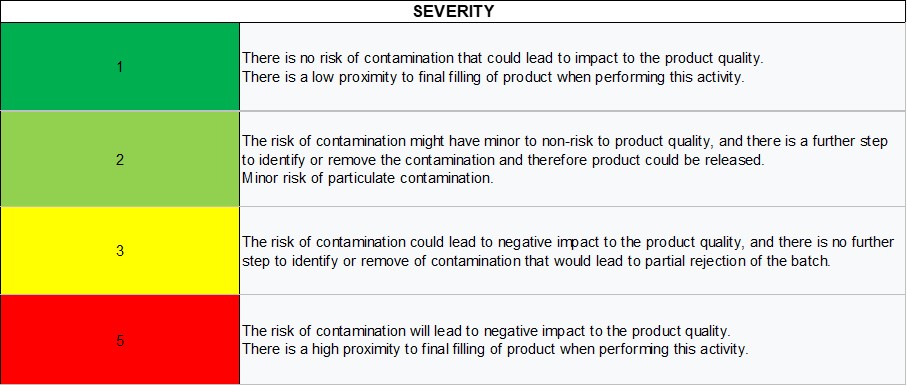

Severity

The severity is defined as a measure of the possible consequences of a hazard (3). The scale proposed uses the following aspects to determine the level of severity:

- Probability of risk to product quality and to patient that could lead to partial or total batch rejection

- Presence of further steps that can help reduce the associated risk

- Proximity to the final filling of product

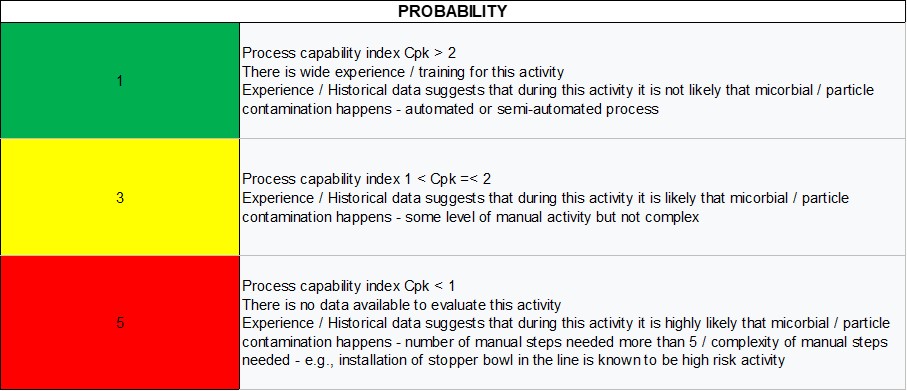

Probability

The probability scale is defined in Table 2. The evaluation should be based on:

- Data collected through previous experience in the facility

- Data coming from environmental monitoring (EM) and particle monitoring

- Data from previous deviations and investigations

- Capability assessment if there is enough data

- Historical knowledge and published literature

- Level of automation—In case of a manual step, how many manual steps are needed and what is the complexity of the manual steps to complete the task?

As defined in Table 2, a rating of 1 means that, during the activity evaluated, it is not likely that microbial, particle or chemical contamination will occur. The type of contamination will depend on the step evaluated. In a cleaning step, for example, the risk is mainly of chemical contamination or cross-contamination. To assess the probability, if there is enough data for a capability analysis, this can be applied. If this is not the case, the scale in Table 2 suggests other options for the evaluation, such as by the level of automation, experience or published literature.

For example, we can evaluate the cleaning step for the stopper bowl considering a common, yet challenging, residue like silicone oil.

- If the stopper bowl is fixed, the cleaning step is done manually. According to Table 2, the probability can be assigned with a rating of 3 or even of 5 depending on how complex this activity is to be performed. This will depend on the size of the bowl and the design of the line.

- If the stopper bowl is detachable, the probability of having issues with the cleaning is lower. The cleaning is usually done in a parts washer using a validated process. The use of laboratory coupon studies can help in designing a robust cleaning process, which will ensure the removal of silicone oil. In this case, the probability of having an unsuccessful cleaning is a rating of 1.

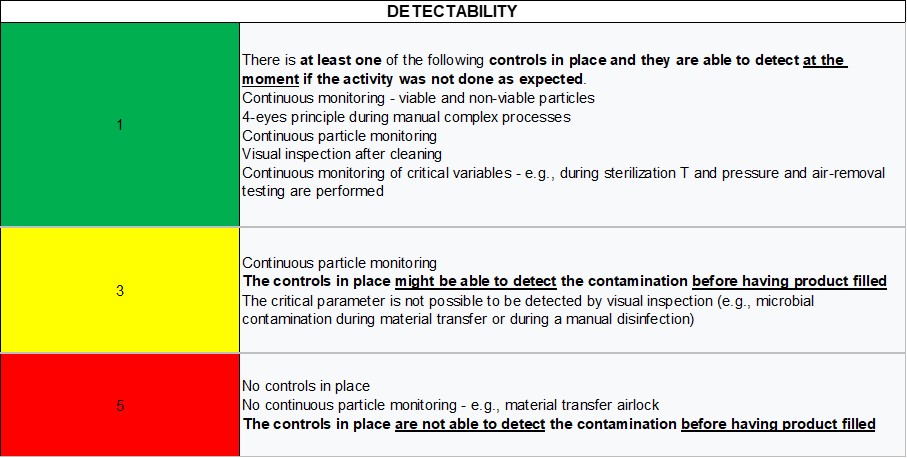

Detectability

The detectability has to do with the controls in place to detect process failures. Controls that can be in place in a cleanroom are:

- Particle monitoring

- Microbial monitoring or EM

- Microbial monitoring through contact plate or settle plate

- Supervision of operators during procedures

- Four-eyes principle

- Visual inspection

- Continuous monitoring of critical variables

Table 3 shows the proposed scale for detectability. The evaluation should be done based on how good the controls in place are to detect the risk at the moment something is not performed as expected. For example, during manual material transfer, the detectability can be assigned a rating of 5 since it is very hard to detect a failure in the process leading to microbial contamination.

Risk Priority Number

The risk priority number (RPN) can be calculated as the multiplication of the probability, severity and detectability of each step. Table 4 shows a proposed scale for the overall risk classification according to the obtained RPN. Based on this scale, the risk can be determined as low, moderate, or high. It can be noted that, from a certain RPN, control measures are needed to reduce the risk. By doing this, only the detectability is going to be impacted. The severity and probability of the risk of the step should remain the same unless a substantial change is done to the process step.

Considerations – Facility Design and Barrier Technology

To assess the risks in each scenario, each step of the lifecycle of the stopper bowl will be analyzed.

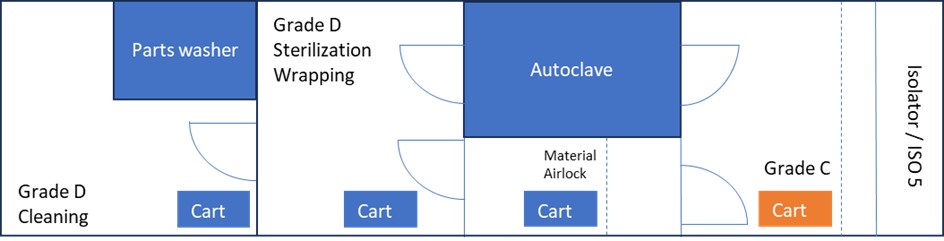

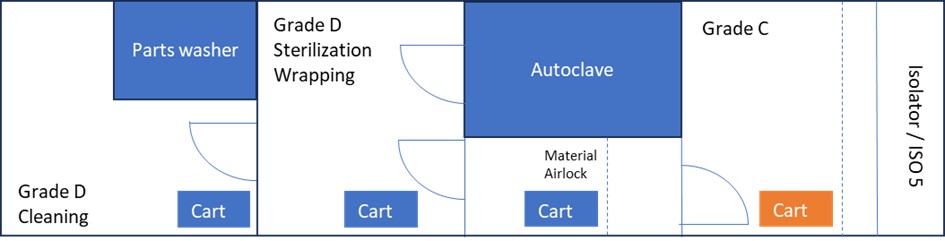

For the purpose of explaining the risks and control measures associated with the stopper bowl within its lifecycle, Figure 2 displays an example of the configuration of a facility. There are two different layouts—with (A) and without (B) a double-door autoclave—that will only impact the way in which the transfer process of the stopper bowl and other indirect surfaces is performed in Scenario 1, as will be explained. There are dedicated carts for Grade D and Grade C areas. An isolator with automated vaporized hydrogen peroxide (VHP) biodecontamination is considered the barrier technology available.

Scenario 1: Stopper Bowl is Detachable

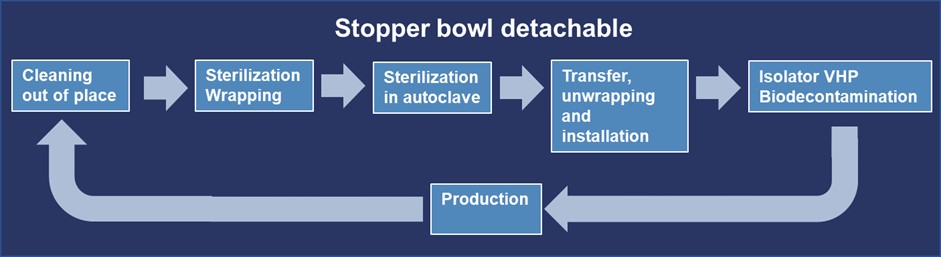

A typical lifecycle of the stopper bowl for this scenario can be seen in Figure 4.

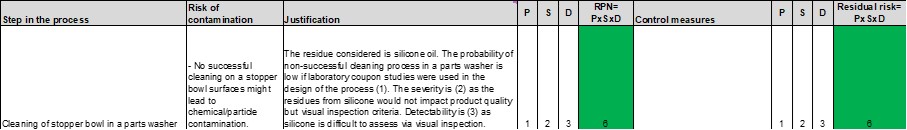

Cleaning of the Stopper Bowl

If the stopper bowl is detachable, it is usually cleaned with a parts washer. This eliminates the risk of poor reproducibility, which must be considered for scenario 2 with non-detachable stopper bowl.

The risk within the cleaning process is associated with:

- How hard is the residue to clean?

- How is the cleaning procedure designed?

The harder it is to clean the residues, the higher the risk of the cleaning process failing. Residues of silicone oil coming from siliconized stoppers are quite common, as are hard-to-clean residues due to their poor solubility in water. The use of formulated chemistries that have different components in the formulation, such as surfactants, chelants and binders, will provide more effective cleaning for hard-to-clean soils (4). An appropriate cleaning procedure, its design based on laboratory coupon studies to support the selection of the right chemistry, concentration, temperature and time, will reduce the risks of failed procedures (4). Further, silicone residue is hard to detect via visual inspection and often not detected by operators. Easier-to-clean and easier-to-detect residues might reduce the risk within this step.

Sterilization Wrapping – Preparation of the Stopper Bowl for Steam Sterilization

The risk of this step is highly dependent on the wrapping material used. The manipulation from operators can also lead to particle and microbial contamination, though it is considered that the operators are well-trained in aseptic processing. Thus, this risk is lower in comparison to contamination coming from the wrapping material.

- If Tyvek is used, the risk of particles is considered low, since peeling open a sealed Tyvek pouch generates less than one-tenth the number of particles (0.5 µ and 5 µ in size) compared to a cellulose pouch with a rating of 5. The probability of risk of particles would be a rating of 1. Severity is considered a rating of 3, as this can affect the product quality although not as severe as for a product rejection. Detectability is considered as a rating of 3 through particle monitoring, for example, giving an overall RPN=9, which falls in the green area.

- If cellulose material is used, the probability of particle contamination is considered as a rating of 3. This would lead to an RPN=27, which falls in the yellow area, corresponding to a moderate risk according to Table 4.

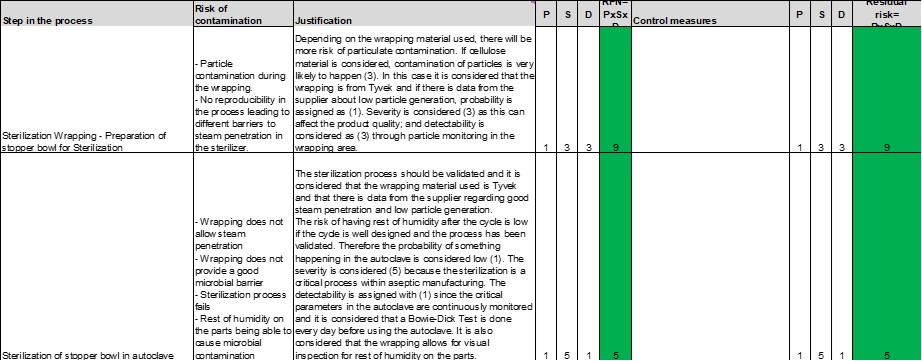

Sterilization of the Stopper Bowl in Autoclave

A validated steam sterilization process with a well-maintained autoclave carries a low risk, as it is considered that a Bowie-Dick Test is used every day before using the autoclave. The risk in this step is also tightly associated with the wrapping material used. If the material considered is Tyvek, and there is data from the supplier on—

- Good steam penetration

- Reproducibility during the wrapping process to ensure the same barrier to steam every time

- Good microbial barrier

- Low particle generation

—then it is considered that the wrapping has a view window to allow the visual inspection of the parts for the rest of humidity after the cycle. The risk can be assessed as very low, giving an RPN=5.

Transfer of the Sterilized Stopper Bowl from Grade D to Grade C

The transfer of materials into and out of the cleanrooms and critical zones is one of the greatest potential sources of contamination (2). The key to minimizing microbial and particulate contamination is to assess the possibilities available at the facility and look into the most practical and appropriate way to mitigate those risks. Different ways to perform material transfer include:

- Sterilization (double-door/ended) or depyrogenation tunnel

- VHP or biodecontamination method

- Removing outer layer of sterilized packaging

- Manual disinfection

The most practical way to minimize contamination risk is to use a double-door autoclave (2), but this is not always possible.

The recommended sterilization wrapping for the stopper bowl when there is no double-door autoclave is a cover plus two sterilization-wrapping bags of flexible Tyvek. In the example in Figure 2 (B), the transfer of the stopper bowl will be done by removing the outer layer of sterilization wrapping. This method is preferred over manual disinfection due to the following:

- It eliminates a manual procedure with all its inherent challenges in reproducibility.

- The manual disinfection in this case is especially challenging since the outer sterilization wrapping layer is flexible and, therefore, difficult to cover with a wipe.

- Removing an outer sterilization layer is faster than wiping with disinfectant, and it bypasses wet-contact times.

The recommended procedure for the transfer of the stopper bowl from Grade D to Grade C is:

- The cart is removed from the autoclave, and the parts are inspected for any condensation.

- The stopper bowl is placed on the cart side Grade D and driven into the material airlock.

- With the help of another operator, and under continuous laminar airflow, the outer layer of wrapping is removed, and the stopper bowl is placed on the cart side Grade C.

- The stopper bowl remains with an inner layer of wrapping and can be stored or be directly installed in the filling line.

Without a continuous particle-monitoring in the material airlock, the step is ranked as moderate to high risk with an RPN=45. It is therefore recommended, if possible, to avoid having to do a manual material transfer and to automate the process with a decontamination chamber or a double-door autoclave.

Unwrapping and Installation of the Stopper Bowl in the Filling Line

This step poses a particular high risk when dealing with isolators, as the surrounding environment is a Grade C environment, for which the operators have a lower degree of gowning in comparison to a Restricted Access Barrier System (RABS), where the surrounding environment is Grade B. For this reason, to mitigate the risks during the unwrapping and installation of the stopper bowl, the operators should wear extra gowning such as face masks, goggles and Tyvek sleeves. On the other hand, isolators provide an “extra layer of protection” due to the biodecontamination with VHP, performed right before production starts. This helps mitigate any risk of contamination that could happen during the transfer of the stopper bowl and the unwrapping and installation process. In recent years, RABS has also employed automated VHP biodecontamination before production starts by applying VHP in the Grade B rooms and Grade A RABS at the same time. The recommended procedure would be:

- The wrapped stopper bowl should be transported with the cart until right before the limit between Grade C and Grade A areas (punctuation line on Figure 2). The unwrapping should happen inside the area between the punctuation line and the isolator doors. In this area, continuous laminar flow should be coming from the isolator Grade A area.

- Continuously under the laminar flow, with the help of an operator, the outer cover of the stopper bowl should be unwrapped.

- Both operators should place the stopper bowl on the line for installation.

- The last cover can be left on the stopper bowl until after the VHP cycle and right before aseptic production starts.

This transfer step is the most critical in this scenario with an RPN=30. The high number is due to a lack of continuous real-time EM that could detect any issues during the procedure. This requires relying on particle monitoring and aseptic process simulation to ensure the procedure is functioning as expected.

As defined in this example, an RPN=30 demands measures to be in place to control the risk such as:

- Supervision by other operators

- Good aseptic technique

- Well-written procedures

This should help in mitigating the risk in the transfer and installation step.

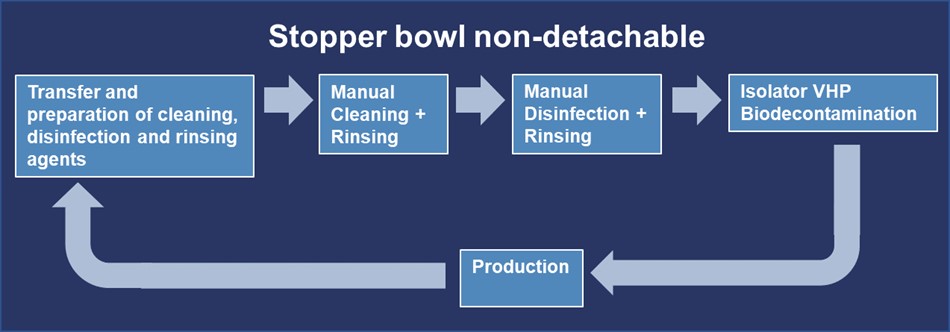

Scenario 2: Stopper Bowl is Nondetachable

In this case, a manual cleaning and disinfection of the stopper bowl can be used as an alternative procedure. A typical lifecycle of the stopper bowl for this scenario can be seen in Figure 8.

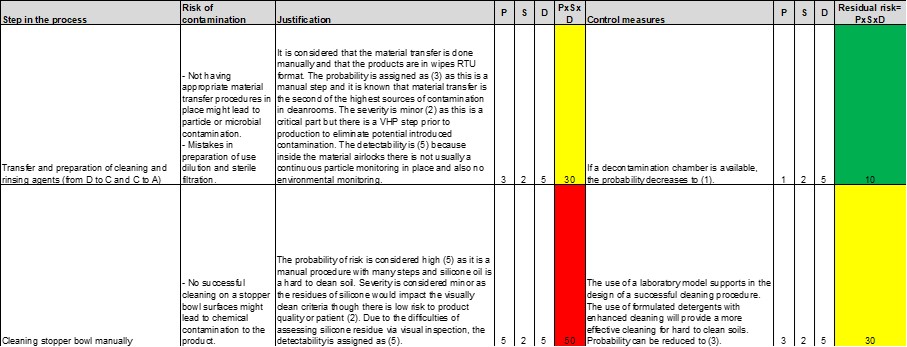

Transfer and Preparation of Cleaning, Disinfection and Rinsing Agents

The cleaning and disinfecting agents used inside Grade A and Grade B areas should be sterile prior to use (2).

The transfer of these materials will depend on the format in which they are packed. If the products used are ready-to-use (RTU) wipes, they come sterile and double-bagged. These can be transferred using the material airlock shown in Figure 2 by removing the first packaging layer inside the Grade D area and placing the wipes on the cart side of the Grade C area. The last packaging layer will be removed inside the isolator or in the material airlock of the isolator, prior to use of the wipes.

In case the product comes in spray form and is double-packed, the same procedure for material transfer can be performed. The spray and trigger may come separately; both are to be transferred in the same way. Right before starting the procedure, the trigger can be pushed into the spray bottle inside the material airlock of the isolator and then transferred inside the isolator.

Sterile polyester wipes can be transferred either by removing the outer packaging layer or by disinfecting the packaging every time it is transferred to a higher classification. If the disinfection method is used, it should be performed in the lower classification area, while the wet-contact times should be observed in the higher classification area of the airlocks.

The risks associated with the preparation of the cleaning and disinfection (C&D) agents will increase if the use-dilution of detergent/disinfectant needs to be prepared and filtered under a laminar flow inside the Grade A area. The more manipulation needed for the preparation, the higher the risks for contamination and compromise of the sterile state of the agent used.

To evaluate the risks of this step, the following need to be considered:

- Use of RTU wipes – low risk on preparation; otherwise, high risk

- Manual or automated material transfer (e.g., with a decontamination chamber)

- Controls in place during the material transfer, such as continuous particle-monitoring in the material airlock

For this example, the material transfer will be considered to be manual and RTU wipes are used. The probability of a risk happening during a manual material transfer is considered as having a rating of 3. Since there is usually no continuous particle monitoring or EM in place in a material airlock, it is difficult to detect if something goes wrong during the process. The only control in place is visual inspection. Detectability is assigned a rating of 5. The severity is classified as 2 because there is a VHP step prior to production to eliminate potentially introduced contamination. This step is identified as middle-to-high risk (RPN=30). If a decontamination chamber is available, the probability would decrease to 1, and the step would have an RPN of 10.

Manual Cleaning of the Stopper Bowl

It is important to understand the possible residues that need to be cleaned to select the right cleaning agent. Hard-to-clean residues such as silicone oil usually need an alkaline-formulated detergent. Other easier-to-clean residues might be cleaned using a neutral-formulated detergent, H2O2, 70% Isopropyl alcohol (IPA) or Water for injection (WFI). When cleaning with a formulated chemistry, WFI or 70% IPA applied in wipes can be used to remove surfactant residue.

The manual cleaning of the stopper bowl will be done with the doors open, unless it is possible using another method. Besides the inherent risks of the manual cleaning itself, other measures are necessary to minimize the risk of particle and microbial contamination during the procedure, such as:

- Laminar flow working throughout the process

- Extra gowning, for example, face masks, goggles, and Tyvek sleeves

- Practice of first cleaning nonproduct-contact areas or low-risk areas, followed by high-risk areas like the stopper bowl in the cleaning procedure.

As a critical indirect-surface area, the cleaning of the stopper bowl needs to be validated using visual inspection and both analytical and sampling methods. Analytical methods will depend on the residue to be traced. Total organic carbon (TOC) analysis can be challenging due to interference coming from IPAs commonly used in these areas. Therefore, HPLC and conductivity methods are preferred. Another challenge is the calculation of a cleaning limit for a stopper bowl where there is no direct contact with the product, but contact with a primary-packaging material.

Manual cleaning introduces the usual risks associated with reproducibility and is more carefully reviewed by authorities. Measures that can be taken to minimize these risks are:

- Procedures should be easy to follow

- Standard operating procedures should be detailed, and operators should be trained frequently

- Procedures should be supervised at a certain frequency or every time (four-eyes principle)

- Monitoring procedures, like swabbing, to confirm the cleaning process was effective should be done after each cleaning or at least with a higher frequency as done in automated cleaning processes (6).

Some of these measures might be challenging to execute, depending on the production schedule, such as frequent training, observations of the process and periodic swabbing of the surface. Nonetheless, a compromise should be found in which the risks can be minimized, and resources are not exceeded.

As mentioned, RTU wipes not only simplify the material transfer but also eliminate the need to prepare the use-dilution inside the Grade A area, thereby minimizing risks and the number of manual activities overall. The use of laboratory coupon studies can help explore and define the right procedure such as how many wipes to use, how many strokes per wipe are needed and which kind of wiping pattern is optimal (e.g., unidirectional overlapping strokes, back and forth). Rinsing with 70% IPA to remove the excess of surfactants can also be simulated in the laboratory.

The main risk during this step is not having a successful cleaning. There is a risk of introducing contamination during this intervention; however, manufacturers with experience in this type of cleaning report that the risk is very low. The probability of this risk should be revised and assessed based on historical data and the experience of each manufacturer as this will depend on the residue, the cleaning agents used, the procedure and the design of the filling line. For this example, the residue is considered to be silicone oil. The probability of an unsuccessful cleaning can be considered a rating of 3 or even a 5 because this is a manual process, and silicone oil is a hard-to-clean residue. Due to the difficulties of assessing silicone residue via visual inspection, the detectability is assigned as a rating of 5. Severity is assigned a 2 rating as this residue would not impact product quality. This gives an RPN between 30 and 50, middle-to-high risk. The probability of this risk can be reduced to rating of 3 if a laboratory model is used to design the cleaning procedure. This would result in an RPN between 10 and 30. If the residue is easy to clean, the probability of having an unsuccessful cleaning can be reduced to a 1, resulting in an RPN of 10.

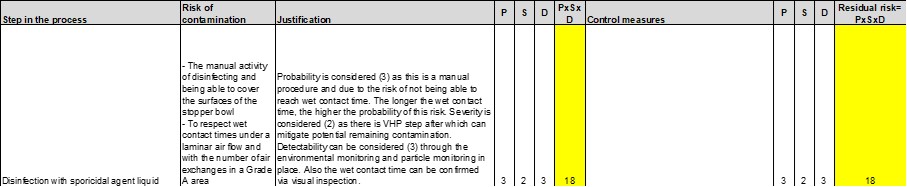

Manual Disinfection of Stopper Bowl

A sporicidal agent is recommended to be used as disinfectant as this is an indirect surface near the final filling of the product. A sporicidal agent, such as a peracetic acid/H2O2 blend, will ensure full microbial inactivation. IPA 70% applied in wipes is recommended as the rinsing method to allow for evaporation after the rinse step is completed.

As the surface of the stopper bowl is in direct contact with stoppers (primary product-contact surfaces), the stopper bowl requires cleaning validation. This means that that the rinsing step should be demonstrated as able to remove the sporicidal agent below a calculated cleaning limit. The sporicidal agent should have a Permitted Daily Exposure (PDE) or Acceptable Daily Exposure (ADE) value available, and the shared surface area should be considered for the calculation of the cleaning limit.

The risks associated with this step include:

- Manual disinfection application and being able to cover the surfaces of the stopper bowl

- Unidirectional overlapping strokes are challenging to perform due to irregularities on the stopper bowl surface

- Longer wet-contact times in a Grade A area—The effectiveness of the disinfection is defined as a certain wet-contact time needed to achieve a certain 10-log reduction (7). In a Grade A area, due to the high number of air exchanges, it is challenging to reach wet-contact times longer than five minutes. For Grade A/ISO 5 areas, however, the acceptable microbial count should be 0 (no growth) (2). According to USP 43, Chapter <1116>, samples with contamination should not exceed 0.1% of the total samples collected. In other words, out of 1,000 samples, 999 should show no growth. This implies that, for example, a 10-minute contact time with a sporicidal agent to achieve a 6-log reduction might not be required. A shorter wet-contact time, based on achievable values, can be validated for a Grade A area, reducing the risk of the contact time not being respected. The effectiveness of the procedure can be confirmed during aseptic process simulation and in disinfectant in-situ testing. (See Figure 10.)

Conclusion

The risk-assessment exercise for both scenarios, involving detachable and nondetachable stopper bowls, aimed to identify the major challenges in each case and determine the best recommendations or control measures to mitigate contamination risks.

It is challenging to reach a conclusion about which scenario poses the lowest risks due to the numerous assumptions made during the analysis. Each manufacturer should arrive at their own conclusions based on their procedures and controls in place. An overview of the advantages, disadvantages and recommendations for both scenarios are given in Table 5.

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Recommendations/Control Measures to Mitigate Risk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1: Stopper bowl is detachable Clean-out-of-place – Sterilization – Transfer – Installation – VHP – Start production | If there is a double-door autoclave, there is only one critical step identified in the process: The unwrapping and installation of the stopper bowl Since the cleaning and sterilization are automated, there is less operator intervention, less risk and more time for the operators for other activities It is compliant with EU GMP Annex 1 | More steps, which probably means more time is needed between production campaigns More “manipulation” of the stopper bowl, and so, higher probability of introducing contamination during the manipulation | Lab coupon studies to design the appropriate cleaning procedure Double-door autoclave or automated decontamination system to transfer the bowl to Grade C, in case of isolator, and to Grade B, in case of RABS. Tyvek wrapping for sterilization with a design that makes it easier for material transfer and installation Well-written and easy-to-follow material transfer and installation procedures |

| Scenario 2: Stopper bowl is nondetachable Transfer and preparation of C&D and rinsing agents – Cleaning and Disinfection in place – VHP – Start production | Fewer steps will require less time between production campaigns Less “manipulation” of the stopper bowl, so less probability of introducing contamination during the manipulation | There are many steps identified as high risk due to the material transfer of C&D agents, which is typically done manually Manual activities are reviewed more carefully by authorities; there should be a well-designed and justified procedure for the manual C&D process to guarantee reproducibility, and the process should be confirmed at a justified frequency (6) Since it is an alternative procedure to the one required by EU GMP Annex 1, additional effort is needed to justify its use | Lab coupon studies to design the appropriate cleaning procedure RTU wipes to make the cleaning procedure easier and minimize the risks during preparation of use-dilution and material transfer Well-written and easy-to-follow C&D procedures Frequent confirmation of the manual cleaning procedure with four-eyes principle and frequent sampling (6) Validation of short wet-contact times for disinfectants achievable inside a Grade A area |

The simplest way to comply with EU GMP Annex 1 is to use a detachable stopper bowl, and new filling lines will meet this requirement. Alternatively, redesigning the production line for nondetachable parts is an option, though it may be prohibitively expensive for some companies. Additionally, the more indirect surfaces that cannot be sterilized, the greater the effort and cost required to redesign the filling line. In such cases, a risk-management approach can justify an alternative procedure, such as manual C&D.

References

- W. El Azab, C. Pierobon. STERIS Webinar – RABS and isolators: Stopper bowl challenges, September 2023.

- EudraLex Annex 1 Manufacture of Sterile Medicinal Products, August 2022.

- ICH Quality Guideline Q9: Quality Risk Management, September 2015.

- G. Verghese, J. Thomas. “Cleaning Agents for Biopharma Manufacturing,” Genetic Engineering News, Vol. 23, March 2003.

- STERIS White Paper “Particulate Contamination is a Concern for Critical Product Contact Surfaces”

- EudraLex Annex 15 Qualification and Validation, March 2015.

- PDA Technical Report Number 70: Fundamentals of Cleaning and Disinfection Programs for Aseptic Manufacturing Facilities, 2015