COVID-19 and the Need for an LAL Alternative

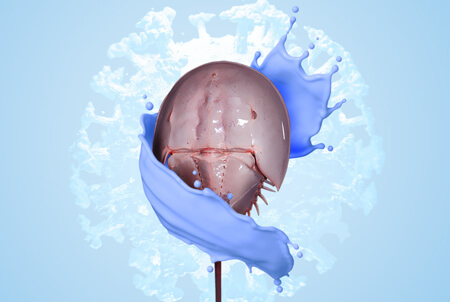

Recent news media and trade journal reports have focused on the sustainability of limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) supply as the world races to vaccinate billions of people and bring an end to the coronavirus pandemic. As members of the Horseshoe Crab Recovery Coalition (HCRC), a group of nearly 40 conservation, business, and healthcare organizations, we would like to share our perspective on the issues surrounding LAL supply, efforts to protect the source of that supply — the American Horseshoe Crab — and the need for a sustainable, animal-free alternative to current endotoxin testing methodologies.

In this article, we focus on the following issues related to endotoxin testing in order to relay important concerns both from a healthcare and a conservation perspective.

- We cannot be sure that there will be a sufficient supply of horseshoe crab blood to meet future demand.

- LAL producers are not conservation experts and are not in the best position to assess the health of this species and relying on the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) to do so is problematic.

- Taking blood from a wild animal, when an animal-free alternative exists, is not consistent with pharmaceutical industry 3R (Reduce/Refine/Replace) principles.

LAL Supply Chain Concerns

LAL suppliers believe the supply of horseshoe crab blood is robust and the supply chain is stable.

The mere fact that the collection of LAL depends on a labor-intensive harvest and bleeding process of a wild animal should alone cause a high level of concern. Bait harvest numbers have declined by approximately 75% over the last 20 years, but biomedical collections have significantly increased — by an astounding 300%. The difference between bait and biomedical collections for 2019 was a mere 3% (1).

There is good reason to be concerned. The Chinese government recently added the Chinese horseshoe crab Tachypleus tridentatus to the country’s List of National Key Protected Wild Animals, owing to a significant decline of the species. The Chinese horseshoe crab is the source of tachypleus amebocyte lysate (TAL) which is the species’ equivalent to LAL. Anecdotal reports are that the decline of Asian horseshoe crabs is leading the pharmaceutical industry to shift global demand for endotoxin testing from TAL to LAL.

In 2019 alone, biomedical harvest of LAL in the United States increased 25% and total mortality increased 30% (1). The biomedical mortality was close to double the ASMFC Horseshoe Crab Fisheries Management Plan’s mortality threshold of 57,500 horseshoe crabs, which the commission suggested should trigger consideration of management action for the biomedical bleeding industry (1). This threshold has been exceeded in 12 of the last 13 years, yet for unknown reasons, the ASMFC has yet to act to better regulate biomedical harvest. The most recent increase, resulting in a mortality estimation of more than 100,000 horseshoe crabs in 2019 alone (1) suggests the possibility that a decrease in TAL may be putting pressure on the LAL supply chain. These numbers do not yet reflect any changes due to the pandemic.

The LAL manufacturers state that they can cover the need for LAL testing for COVID-19 vaccines, mentioning the millions of doses already distributed. It must be remembered that outside of the U.S. and several other developed nations, we are still in the early stages of the vaccination process. As of June 23, 2021, only 22.2% of the 7.8 billion people in the world have received at least one dose. In the developing world, that number stands at just 0.9% (2).

Will the LAL suppliers be ready for billions, not millions, of doses? It is impossible to know, because the suppliers do not reveal how many horseshoe crabs are required to manufacture a batch of LAL or how much of either they have in stock.

Conservation Concerns

LAL producers are not wildlife conservation experts, and the ASMFC itself has had a mixed record when it comes to species management. For instance, striped bass, a much better monitored and far more commercially valuable species were found to be unsustainably harvested based on 2017 data, and ASMFC is just now considering regulations that would not be in place until next fishing season. That means five years of continued decline of the species before corrective actions are taken. It is just one such example of delayed action on the part of ASMFC.

The population dynamics of horseshoe crabs are poorly understood in comparison to striped bass, especially outside of Delaware Bay. Such delay in identifying and rectifying any future declines of horseshoe crab populations could have significant, reverberating impacts for pharmaceutical supply chains and ecosystems alike.

While it is true that horseshoe crabs are not yet endangered, they remain under significant threat. For example, in the Delaware Bay, horseshoe crab populations have declined by two-thirds from two decades ago and have yet to recover. Crab populations outside the Delaware Bay are believed to have fared even worse.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature has classified the American Horseshoe crab as “vulnerable”, meaning the species is threatened with global extinction (3). Therefore, the species is clearly not showing the signs of improvement the LAL manufacturers are claiming.

Other factors also indicate that horseshoe crabs are not thriving. For example, long-distance migratory shorebirds that depend on healthy horseshoe crab eggs as fuel have declined by 70% since 1973 (4). One of them, the Red Knot, is now listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. The loss of crabs and eggs was causal in Red Knot decline, and this listing includes the effects of biomedical bleeding of horseshoe crabs. A true consideration of the sustainability of LAL must also consider the role the species plays in supporting struggling populations of shorebirds and its estuary ecosystems.

Sustainability Concerns and the 3Rs

More than 600,000 horseshoe crabs are captured annually for biomedical bleeding, which involves insertion of a needle into the animal’s heart and removing up to 40% of its blood. After the blood is drawn, the crab is returned to the water. Estimates suggest that up to 30% do not survive the process (5). A 2013 study also showed that after bleeding, horseshoe crabs had a 33-66% reduction in overall activity and the females demonstrated markedly lethargic behavior and failed to spawn entirely (6). This independent research indicates it is very likely the ASMFC estimates understate both mortality and long-term effects of biomedical bleeding on horseshoe crabs.

LAL industry practices unfortunately do not include basic conservation or transparency practices such as public disclosure of catch or release sites or true mortality counts, and they have not committed to helping restore horseshoe crab populations to previous levels. The most important conservation measure would be to phase out the blood harvest of a wild animal in favor of a more sustainable, scalable, and humane alternative that would help the pharmaceutical industry advance its 3R principles.

When Russell and Burch proposed the 3R principles in 1959, they called the eventual replacement of animal-based research, education, and testing the “ultimate goal” (7). The European Union (EU) first introduced legislation protecting animals used for experimental or other scientific purposes in 1986 and updated it in 2010. Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes spells out the 3Rs and makes systematic consideration of these principles a firm legal requirement when animals are used for scientific purposes in the European Union (8).

A major global pharmaceutical company, Eli Lilly and Co., has decided to make the switch to a synthetic alternative to LAL, both for a supply-chain sustainability and corporate responsibility rationale. The synthetic product is currently being used in endotoxin testing for four FDA-approved medicines, including two COVID-19 therapeutics, as well as active pharmaceutical ingredients, clinical samples, and other pharmaceutical components.

This synthetic alternative, known as recombinant factor C (rFC), is gaining acceptance by many pharmacopeias around the world, including earning compendial status in Europe and China with a path in place for what we hope will be full compendial acceptance by the U.S. Pharmacopeia and global harmonization.

In a technologically advanced society, the pharmaceutical industry should not have to rely on horseshoe crab blood when an effective substitute exists. As we have described, supply chain concerns are real, conservation concerns are real and sustainability concerns and lack of adherence to the 3R principles are real as well.

To assuage these concerns, scientific and regulatory communities, and the pharmaceutical industry should work together to ensure acceptance and more widespread use of rFC, adding to the toolbox for bacterial endotoxin testing.

References

- Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. 2020. Review of the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Horseshoe Crab (Limulus polyphemus). 2019 Fishing Year.

- https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (accessed 7th May, 2021)

- Smith, D. R., M. A. Beekey, H. J. Brockmann, T. L. King, M. J. Millard and J. A. Zaldivar-Rae. 2016. Limulus polypheums. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T11987A80159830. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T11987A80159830.en

- North American Bird Conservation Initiative. The State of North America’s Birds 2016 (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2016).

- Leschen, A. S. and Correia, S. J.(2010) ‘Mortality in female horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus) from biomedical bleeding and handling: implications for fisheries management’, Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology, 43: 2, 135 — 147, First published on: 29 April 2010 (iFirst)

- Anderson, R. L., Watson, W. H., and Chabot, C. C. (2013). Sublethal behavioral and physiological effects of the biomedical bleeding process on the American horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus. Biol. Bull. 225, 137–151. doi: 10.1086/BBLv225n3p137

- Russell, W. M. S., Burch, R. L.. 1959. The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique. London, UK: Methuen.

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2010:276:0033:0079:en:PDF(retrieved 2-Feb-2021)

Elizabeth Baker, Esq., is the Pharmaceutical Policy Program Director for the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, a nonprofit working for more effective, efficient, and ethical medical research, product testing, and training. Elizabeth leads the Physicians Committee’s work to modernize policies to support the use of scientifically valid nonanimal and human biology-based approaches in drug development.

Elizabeth Baker, Esq., is the Pharmaceutical Policy Program Director for the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, a nonprofit working for more effective, efficient, and ethical medical research, product testing, and training. Elizabeth leads the Physicians Committee’s work to modernize policies to support the use of scientifically valid nonanimal and human biology-based approaches in drug development.  Zach Cockrum is Director of Conservation Partnerships, Northeast Regional Center for the National Wildlife Federation. He works alongside the National Wildlife Federation’s state-based affiliates in the Northeast and beyond to support conservation outcomes including restoring the ecological function of marine fisheries. These efforts include supporting management of Atlantic menhaden for their role in the ecosystem, helping restore Atlantic herring populations, helping launch the Horseshoe Crab Recovery Coalition and ensuring offshore power is developed responsibly by considering potential impacts on fish, marine wildlife and the recreational fishing industry. Zach has a Master of Science in Environmental Sciences and Policy degree from Johns Hopkins University.

Zach Cockrum is Director of Conservation Partnerships, Northeast Regional Center for the National Wildlife Federation. He works alongside the National Wildlife Federation’s state-based affiliates in the Northeast and beyond to support conservation outcomes including restoring the ecological function of marine fisheries. These efforts include supporting management of Atlantic menhaden for their role in the ecosystem, helping restore Atlantic herring populations, helping launch the Horseshoe Crab Recovery Coalition and ensuring offshore power is developed responsibly by considering potential impacts on fish, marine wildlife and the recreational fishing industry. Zach has a Master of Science in Environmental Sciences and Policy degree from Johns Hopkins University. Dr. Lawrence Niles received a BS and MS at Pennsylvania State University, and a Ph.D. from Rutgers University in Ecology and Evolution. Larry’s started his 40-year career as a regional game biologist in Georgia and afterwards spent 25 years as chief of the Endangered and Nongame Species Program. In 2006, Dr. Niles started his own company to pursue independent research and habitat restoration in Delaware Bay, Cape Cod, Florida, Texas, San Francisco Bay, the Canadian Arctic, French Guiana, Brazil, and Chile. He is a founding member of the Horseshoe Crab Recovery Coalition and on the board of the National Shorebird Council and Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network.

Dr. Lawrence Niles received a BS and MS at Pennsylvania State University, and a Ph.D. from Rutgers University in Ecology and Evolution. Larry’s started his 40-year career as a regional game biologist in Georgia and afterwards spent 25 years as chief of the Endangered and Nongame Species Program. In 2006, Dr. Niles started his own company to pursue independent research and habitat restoration in Delaware Bay, Cape Cod, Florida, Texas, San Francisco Bay, the Canadian Arctic, French Guiana, Brazil, and Chile. He is a founding member of the Horseshoe Crab Recovery Coalition and on the board of the National Shorebird Council and Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network.  Dr. David Mizrahi earned his Ph.D. in Zoology at Clemson University. For the last 20 years he has held the position of Vice-president for Research and Monitoring at New Jersey Audubon. Dr. Mizrahi’s area of expertise is the ecology and conservation of shorebirds with a primary focus on Semipalmated Sandpipers and other shorebird species that winter in northern South America and migrate through the western Atlantic region. Since 1995, he has conducted important research on the ecology and behavior of shorebirds using soft-sediment habitats in Delaware Bay, including investigating the relationship between horseshoe crab egg availability and weight gain potential in Semipalmated Sandpipers, relationships between habitat use and foraging strategies, and migration phenology and connectivity using nanotag technology.

Dr. David Mizrahi earned his Ph.D. in Zoology at Clemson University. For the last 20 years he has held the position of Vice-president for Research and Monitoring at New Jersey Audubon. Dr. Mizrahi’s area of expertise is the ecology and conservation of shorebirds with a primary focus on Semipalmated Sandpipers and other shorebird species that winter in northern South America and migrate through the western Atlantic region. Since 1995, he has conducted important research on the ecology and behavior of shorebirds using soft-sediment habitats in Delaware Bay, including investigating the relationship between horseshoe crab egg availability and weight gain potential in Semipalmated Sandpipers, relationships between habitat use and foraging strategies, and migration phenology and connectivity using nanotag technology.  Ryan Phelan is the Co-founder and Executive Director of Revive & Restore, the world’s leading nonprofit organization focused on bringing biotechnologies to conservation. As a serial entrepreneur living in the San Francisco Bay Area, Ryan founded and successfully sold two innovative health-tech companies—DNA Direct and Direct Medical Knowledge—both designed to empower medical consumers. Since co-founding Revive & Restore in 2012, Ryan has led the organization in its mission to enhance biodiversity through the genetic rescue of endangered and extinct species.

Ryan Phelan is the Co-founder and Executive Director of Revive & Restore, the world’s leading nonprofit organization focused on bringing biotechnologies to conservation. As a serial entrepreneur living in the San Francisco Bay Area, Ryan founded and successfully sold two innovative health-tech companies—DNA Direct and Direct Medical Knowledge—both designed to empower medical consumers. Since co-founding Revive & Restore in 2012, Ryan has led the organization in its mission to enhance biodiversity through the genetic rescue of endangered and extinct species.