Drug Shortage is a "Wicked Problem"

Science, Reliance and Collaboration is Key for Public Health

Drug shortage is undeniably a big problem that impacts public health around the globe. Anyone involved in pharmaceutical manufacturing and its regulation knows that the problem is complex and has more than one root cause. One of the chief problems is the reality that current global regulatory complexities and very limited collaboration among global regulatory bodies on this matter tend to incentivize companies to maintain status quo in their operations rather than continually improving processes and technologies, which in general would result in a reliable uninterrupted supply. Unfortunately, we have not yet found a sustainable solution globally.

The good news is solutions exist to improving drug product availability and encouraging innovation and continual improvement in our industry. But it requires that we start by defining the problem, acknowledging its complexity, and begin working together in a fundamentally different way globally. Primarily, industry and regulatory authorities must find better ways of handling manufacturing-related changes after the initial drug product approval; changes we collectively call post-approval changes (PACs).

This is a call to action. Reality has consistently shown that the current situation is not sustainable. This is a call to action for all relevant stakeholders in the pharmaceutical industry, regulatory bodies and the political system to come together in realizing our common objective of assuring global drug product (medicines) availability and public health by applying science and reliance more effectively. If we do not take action, the situation will get worse.

Let’s agree on three things first:

- One, patients should always expect medicines to be available when needed and of the highest quality, safety and efficacy

- Two, manufacturers should possess a robust pharmaceutical quality system (PQS), manage new knowledge well, improve processes and methods continually using effective science and risk-based approaches, introduce new and better technologies, and do their best to avoid manufacturing quality related problems

- Three, regulators should work collaboratively with manufacturers for solutions that improve public health in a globally sustainable and holistic way

The Current Post-Approval Change Paradox and the "Wicked Problem

If we can agree on these three things, why is it that today we have the following paradoxes for PACs?

- The cGMPs require facilities and processes to be current, yet even for simple PACs it takes up to five years to get global approval for what will make the facility or process current

- Improvements are intended to reduce risks, yet the long PAC approval timelines delay risk reduction

- Improvements may be intended to assure better availability of drug products, yet the long PAC approval timelines hinder availability

- Changes in high tech industries usually happens in months, whereas in the pharma industry changes are measured in years

The PAC Paradox has stifled manufacturing innovation across the industry, which has resulted in aging facilities replete with outdated process controls and equipment. In many instances of drug shortages, these conditions are the direct cause. Often the drug shortage conversation goes in the direction of manufacturing quality issues as the root cause, and it is true that we as an industry must do much better at avoiding these problems. However, when operating aging facilities, manufacturing quality problems are manyfold more frequent and less predictable than when using state-of-the-art facilities and processes. Even if a company wants to improve and make facilities “current,” this in many cases takes up to, or even more than, five years due to the PAC complexity as listed above.

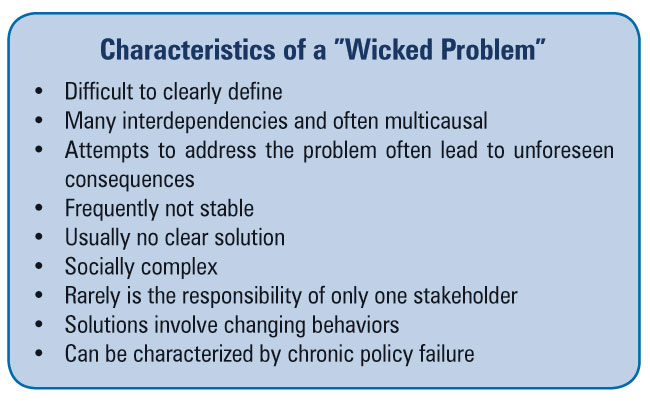

Although many attempts have been made and are being made currently, drug shortages are proving to be a “difficult to resolve” issue, which is also the definition of a “wicked problem" (1,2).

We cannot solve a “wicked problem” by continuing to approach the issue in a linear way, looking only at individual stakeholder angles and most often narrowing the scope to specific cases or instances. We need to recognize drug shortage as a wicked problem, or we may not find sustainable solutions.

Wicked problems need to be addressed in a holistic way rather than from just one of the many stakeholders’ perspectives—some of which can actually be conflicting with each other. Stakeholders must work together to ensure a full understanding of the problem and to share a commitment to possible solutions. Because wicked problems have no simple identifiable root cause, and often there are interactions between several causal factors, solutions require broader, more collaborative and innovative approaches. And these solutions are often not easily identifiable as “right” or “wrong” but rather can be considered “better” or “worse.”

It is time to think and work differently. We must be more collaborative, innovative and flexible, work across boundaries, actively engaging all stakeholder groups, consider the big picture—all of which require that we change our focus away from a local or singular view and, instead, see the problem from a global perspective. Note: This doesn’t mean that we each should continue to improve for issues that are truly “local.”

Regulatory Reliance: Relying More on Each Other

Today, while pharmaceutical companies are highly globalized, drug product PAC assessments are national, and the approval processes differ from country to country. The PAC processes vary in terms of reporting level/requirements and timelines for assessment.

On the surface this might not seem to be a problem. Indeed, for a specific change in an individual country seen in isolation, it might not be, but when that change is to be approved in as many as 100+ countries individually, it becomes complex. A simple change can take up to five years or more from first to last approving country. Companies introduce several changes every year as a natural part of the lifecycle. With this elongated approval cycle, these changes create manufacturing challenges and logistical nightmares. The world is now a “global village.” But global PAC timelines simply cannot keep up with the pace of technological and general change. Past solutions are today’s problems.

This can be demonstrated by discussing a real-life example. For one well known, “tried and tested,” pentavalent vaccine in one year, the manufacturer was forced to produce 83 batches according to 55 different manufacturing versions because of this PAC complexity. On top of that, the 83 batches had to be supplied to over 100 countries allocated based on which country had approved which change. And at the end of the day, all these batches were produced to meet the same product specification!

When you look at PACs from a holistic view, 100+ individual and independent health authority assessments for every single change simply does not make sense from a quality, safety and efficacy perspective, assuming that each of these assessments is thorough and complete. There is a tremendous opportunity for better utilization of resources both at the regulatory and company level at no cost to the quality of the medicines. It is definitely time for global regulators to start working together toward a state of mutual reliance—and for the industry to be more proactive in helping them to do so.

Indeed, regulatory reliance is a topic that is starting to emerge in the current debate. It means that one regulatory body can rely on a quality, safety and efficacy assessment made by another regulatory body for a specific PAC. For instance, if Japan has assessed the introduction of a new piece of equipment and determined that it is acceptable from a quality, safety, and efficacy perspective, the U.S. FDA could decide to rely on this assessment, saving time and resources for an additional review and approval of the same PAC.

WHO, through the World Health Assembly Resolution 67.20 (3), is encouraging health authorities to more actively rely on each other. This type of reliance is not widely accepted, however, and, in actuality, many countries are increasing regulatory oversight, which means that the problem is growing with the likely consequence of further drug shortages.

Positive examples of global regulatory bodies’ reliance on each other do exist. COFEPRIS, the Mexican regulatory authority, relies to a large extent on the assessment done by other specified regulatory bodies for new applications. This has led to significant improvement in medicines approvals for the betterment of Mexican public health (4). In the European Union, one country serves as the representative (Rapporteur) and another as Corapporteur for certain products, and the rest of the States in the EU can give their input if they have any for the individual PAC.

From a scientific perspective, assessing a PAC with respect to quality, safety and efficacy is not dependent on nationality or geographic borders. From a holistic point of view, it would make more sense to have health authorities rely on each other for this scientific assessment and free up resources in an already resource-constrained health care system. For patients, this approach would be the same in terms of product quality, but due to the simplification of the supply chain logistics, the likelihood of drug shortage would be lower then in the current system. Industry’s role would be to help encourage introduction of good regulatory reliance practices worldwide.

Let’s be Practical about Innovation

Let’s talk about innovation for a minute. Take the example that all biologics products must be tested to ensure that they do not contain adventitious agents. The testing has historically been done using traditional test methods, but modern Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) technologies have recently been developed. PCR is faster (lead time reduced from days to hours) and more sensitive in detecting adventitious agents than traditional tests. Objectively, PCR is an improvement from a risk-to-patient and product-quality perspective. Companies should be encouraged to introduce new technologies like PCR. However, faced with five years from submission to final health authority approval and the need to test product by both technologies until approved in all countries, many companies think twice about introducing an innovation like PCR simply because it is too costly and cumbersome.

When the company speaks with health authorities, individually they are, in my experience, supportive, but the wickedness about introducing new technologies is that the company needs to sometimes have conversations with 100+ health authorities, each having their own process in place for the assessment. The complexity of the current regulatory landscape is in actuality a barrier to the introduction of new technologies, and it is understandable that some companies shy away from advancing their technologies or improving their manufacturing processes at the pace they actually would like to. The result? Aging facilities, processes and methods, where daily operations become more and more challenging as time goes by.

I started this article by suggesting that companies continually improve their processes and methods, but as written above, the current PAC complexity is slowing this down drastically—even when it can be objectively demonstrated that the change improves product quality, safety or efficacy. So what can we do about this if we try to think more holistically about the problem? In my view, the answer must include a better science- and risk-based approach to changes than is the case today.

Applying a Science and Risk-Based Approach to Post-Approval Changes

I’m often struck when speaking with colleagues, both members of industry and regulators, that we are all very passionate about patient and public health and this passion drives our decisionmaking, yet we are facing many drug shortage problems. I am confident that if we work together globally to reduce the complexity of PACs we will also drastically reduce the wicked problem of drug shortage. We must leverage our resources, collaborate much more, set up new processes for PAC management, and change behaviors where this is needed to achieve our common objective. Our decisionmaking methodology must be rooted in sound science and the application of modern risk-based principles. Ironically, these principles are already developed and expected to be implemented in our daily GMP operations, but have not yet been applied to PAC assessments.

Let’s assume that a company can demonstrate in theory, design and in practical application that its PQS is robust, has a solid approach to quality risk management, and that changes can be assessed for effectiveness in a sound manner. Now, if that company applies a science-and risk-based approach to a PAC and shows that the post-change risk to product quality is less than the prechange situation and/or that product availability is improved, shouldn’t it be allowed to make this change immediately or with very short prior notice to health authorities? I would say “yes”—and a group with representatives from both industry and global regulatory bodies are discussing this topic currently (5). Today, however, that is not the case. Each regulatory body currently assesses each change individually to safeguard public health in the geographic area/country they represent. The solution here is to allow a more science- and risk-based approach to PAC, which in practice would mean that for companies with a robust PQS, many PACs could be “downgraded” in terms of notification to authorities, and thus facilitate continual improvement and drug product availability.

A Call to Action: Recognize and Treat Drug Shortage as a Wicked Problem

Drug shortage is a very present and very complex problem highly resistant to a solution. A primary contributor to the problem is how we handle PAC globally, which makes supply logistics highly challenging and also slows down innovation and continual improvement. Companies should be encouraged to continually improve methods, facilities, equipment and technologies. Change is natural, and continual improvement to current situation should be encouraged.

Realizing our common objective of assuring global drug product (medicines) availability and public health globally can only be done through dialog to achieve a shared understanding of the drug shortage wicked problem and a shared commitment to the possible solutions, which in my opinion must include a more effective application of science and reliance for PACs.

It is time for action, and for not simplifying this problem and not blaming one single cause. This is a wicked problem. We can all do better, and much better together. I am in for the change—are you?

References

- Rittel, H.W.J., and Webber, M.M. “Dilemma in a General Theory of Planning,” Policy Sciences 4 (1973) 169.

- “Tackling Wicked Problems,” Australian Public Service Commission, 2007

- WHA 67.20 – Regulatory System Strengthening for Medical Products. WHA Resolution; sixty seventh World Health Assembly, May 24th, 2014

- Toledo-Javier, A. “COFEPRIS: Pharmaceutical Policy to Increase Access.” Presented at the 2015 PDA Manufacturing Science Workshop, Washington, DC, September 2015.

- ICH Q12: Technical and Regulatory Considerations for Pharmaceutical Product Lifecycle Management, ICH, draft document for public comments expected in 2017

The views expressed above are those of the author, not those of Sanofi Pasteur or PDA.