Knowledge Management and its Relation to Data Integrity

Since the publication of the International Counsil for Harmonization Q10: Pharmaceutical Quality Systems guideline in

2008, knowledge management has been viewed, along with quality risk management (QRM), as an enabler or foundation of a quality management system.

Since the publication of the International Counsil for Harmonization Q10: Pharmaceutical Quality Systems guideline in

2008, knowledge management has been viewed, along with quality risk management (QRM), as an enabler or foundation of a quality management system.

While QRM has received extensive attention through its own ICH guideline, knowledge management (KM) has only recently begun to garner a similar focus. KM is defined in ICH Q10 as a systematic approach to acquiring, analyzing, storing and disseminating information related to products, manufacturing processes and components, and dictates that product and process knowledge should be managed from development through the commercial life of the product up to and including product discontinuation (1).

Quality system managers and other professionals have raised questions about how data integrity (DI) is related to KM, especially as DI issues continue to be an emphasis in U.S. FDA inspections due to recurring findings of noncompliance. DI refers to the completeness, consistency and accuracy of data throughout its lifecycle. This raises critical questions:

- What is the relationship between KM and DI? Does one influence the other?

- How important is DI to KM?

- How can KM improve DI?

Although the ICH Q10 guideline did not explicitly address DI in its 2008 publication, we can acknowledge in a very basic way that data generated by or in support of GxP processes, systems and decisions is required to comply with DI requirements to be considered reliable. It is logical, then, that DI is not only required but foundational to KM, which aims to make good and acceptable use of GxP data. However, the relationship between DI and KM does not end there.

After ICH Q10, numerous guidelines have tackled the topic of DI in the context of regulatory expectations and industry best practices, particularly for hybrid approaches (both paper and electronic data) to documentation.

These guidances have emphasized the importance of Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original and Accurate ALCOA+ and enumerated how these characteristics apply to classic, paper-based documentation as well as electronic, computer-based information. The "+" extension to ALCOA encompasses the broader use of data in different contexts, specifically, Complete, Consistent, Enduring and Available.

The Relationship

Some specialists view DI more narrowly, focusing on the data itself remaining unchanged from its source capture. In contrast, others use it holistically, such as a proxy for data quality, including attributes akin to ALCOA+ (e.g., timely, actual, unambiguous, etc.). For example, the current PIC/S guide, PIC/S Good Practices for Data Management and Integrity in Regulated GMP/GDP Environments, makes repeated reference to data quality and, at times, uses the term interchangeably with data integrity (2). However, the two terms are technically defined quite differently. Further, the term data governance has also made its way into the mix, adopted by health authorities worldwide and typically defined as “the total of arrangements that assure data integrity” (3). It is widely understood that the integrity of data is best enabled through roles, responsibilities and holistic organizational, procedural and technical controls integrated and managed within an organization’s quality management system.

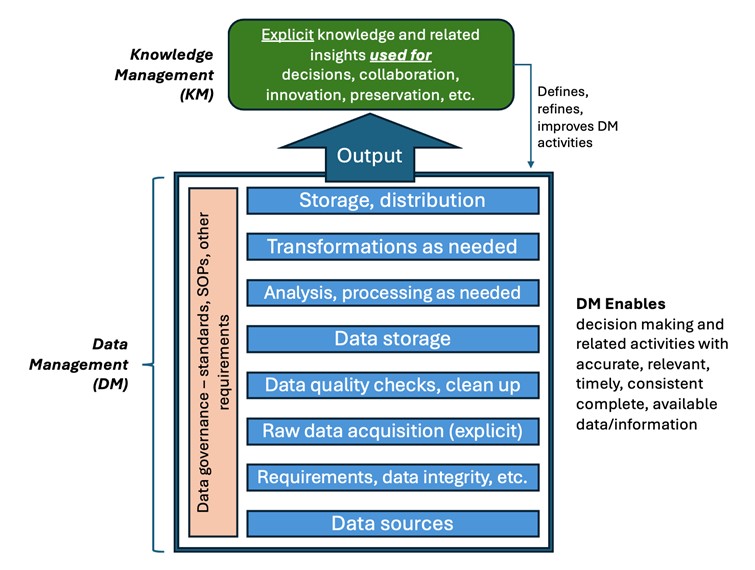

Thus, to understand and leverage the relationship between DI and KM, it may be most impactful to refer to data management (DM) as a term that includes data governance (The authority and control of data assets throughout the data lifecycle. It includes policies and procedures for data collection, processing, storage, use and destruction. It ensures DI, security and compliance with regulations, as well as supports informed decision-making throughout the drug development and manufacturing processes.), DI and data quality. If ICH Q10 was published today, we might imagine DM as a key enabler alongside KM, a discipline in its own right with a set of principles, elements and practices that can be leveraged with KM. Done well, DM supports organizational KM in enabling the right people to make the right decisions at the right time and within the right context, thereby reducing risks to patient safety and assuring GxP compliance.

A simple model (see Figure 1) may be useful for understanding, but keep in mind a quote attributed to George Box: “All models are wrong, but some are helpful.”

Ways that data management supports knowledge management

As more context is added, data becomes information, and information becomes explicit knowledge, finally contributing to understanding. In particular, data management, which includes governance activities, data quality checks and adherence to DI requirements, provides consistent and reliable data. This ensures comparability, reduces confusion and prevents databases' “garbage in, garbage out” condition. It enables the detection of anomalies or data risks in clinical studies, and it allows the factful evaluation of suspicious data in process and analytical development. Too often, however, the auditing/verification of data and the associated DI controls often lack this quality check (1).

In summary, to take appropriate actions, make timely and correct decisions and acquire valid insights and understanding, key knowledge management pathways are dependent on effective DM. How this can be accomplished throughout the knowledge management cycle is described next.

Ways that knowledge management supports data management

As data is acquired, it enters the knowledge lifecycle. One lifecycle is described in the three-phase model, adapted from IBM, that identifies three pillars of KM: Knowledge Creation (e.g., generation of method validation data for a proposed test method), Knowledge Storage (e.g., saving and retrieving information from a LIMS) and Knowledge Sharing (e.g., assembling the appropriate data and narrative to support a proposed test method in a regulatory submission)(4).

KM is often viewed as a theoretical model that describes what should happen to ensure that the organization has the competence it needs to achieve its objectives. DM, on the other hand, is a tactical model for how an organization collects, organizes, stores and protects data as an important resource. DM encompasses the practices required to ensure DI and the responsibilities and roles needed to implement these practices by a competent organization.

The relationship(s) between KM and DM are shown in Table 1. As mentioned earlier, KM can refine DI practices (and other elements of DM) so the outputs are fit for use. The impacts of the following organizational attributes on ALCOA+ characteristics are shown for each of the three KM pillars:

- People: Emphasizes the role of individuals in recognizing the importance of KM, and their participation in creating, storing and sharing knowledge.

- Process: Describes the systematic methods and tools that support each phase of the KM cycle.

- Technology: Details on how technological solutions can aid in capturing, storing and sharing knowledge effectively.

- Governance: Highlights the policies, support structures and incentives necessary to maintain and enhance KM practices.

| KM Phase | People | Process | Technology | Governance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Creation | Employees understand knowledge – both explicit and tacit as a valuable asset that needs to be collected contemporaneously with an activity and be available. | Standardized methods and tools for knowledge creation are implemented contributing to accurate, contemporaneous, consistent data. | Technology facilitates capturing and documenting knowledge effectively: accurate, consistent and attributable. | Governance ensures support for knowledge creation through policies, sponsorship and resource allocation; defines who has ability to create, modify, delete data and be attributable. |

| Knowledge Storage | Knowledge is seen as a valuable asset; employees are trained to store knowledge systematically to that it is enduring and available. | Processes ensure that knowledge is documented and stored in a retrievable manner so that it is enduring and available. | IT systems support efficient storage and retrieval of knowledge ensuring that it is correct, enduring and available. | Governance ensures adherence to standards for curation and retrieval so that it is accurate, completed consistent, enduring and available. |

| Knowledge Sharing | A culture of knowledge sharing is fostered, and employees are incentivized to share their expertise: attributable and available. | Processes facilitate the dissemination of knowledge across the organization: complete, enduring and available. | Technology enables easy access and sharing of knowledge: accurate, complete, enduring and available. | Governance establishes rewards and recognition systems to encourage knowledge sharing and continuous improvement as well as who can access it: attributable, available, accurate, complete and enduring. |

New technology tools can also impact the process used in the three KM phases. For example, having other users comment upon data that has been created and is being stored can make it more valuable. This would be like inviting travelers to comment on a hotel review or home chefs to share their modifications to an online recipe. The underlying review or recipe is not changed, but comments from other knowledgeable stakeholders add value.

Some Illustrative Examples: KM and DM

Three examples may be useful in showing the connections between KM and DM (i.e., including data governance, data integrity, and data quality).

Example 1

Knowledge is often characterized as being explicit – that is, it can be found in a procedure, a report, a video, training material, etc. In addition, it could be tacit – existing in someone’s personal knowledge and experience (in the person’s brain). Another characteristic of knowledge is that it can be “leaky” meaning that knowledge – often tacit – can leave an organization when the person leaves (5).

This is a significant risk to owners of pharma products, particularly when the product is made by a third-party since the submission owner has even less insight into the knowledge that is acquired. Even for manufacturers, it is extremely difficult to capture all the critical tacit knowledge elements when someone retires or leaves the firm suddenly. If a strong DM program is in place, it may be possible to rebuild this lost knowledge. It is also important to have explicit documented rationales for why something was done, for example, the level of validation that was executed. Having complete, accurate, consistent and enduring information available when needed is an important, high-value asset. Here, DM contributes to all three phases of KM and reduces the risk of handling product issues uninformed and naively.

Example 2

Guidelines and regulatory requirements mandate initial validation and periodic revalidation of aseptic processing activities. Due to the high level of contamination risk associated with aseptic processing, this activity is scrutinized during health authority inspections, making the design and execution of the aseptic process simulation (APS) critical. An important word here is simulation: the validation exercise (i.e., the APS) “should imitate as closely as possible the routine aseptic manufacturing process and include the critical manufacturing steps” (6). This means that there needs to be accurate data available concerning manipulations and interventions that represent routine and worst-case operations, which is a tenet of all knowledge management programs. This data is often recorded by hand or electronically contemporaneously and needs to be complete and accurate, including the length of time the intervention takes. Using standardized language when recording interventions allows for improved DI (e.g., provides a more accurate picture of how often a particular intervention is performed). This data allows one to develop a risk-based understanding of interventions that can be used to create or update the APS protocol that is executed. AI may help predict or identify additional or worst-case interventions (KM and AI is the topic of an upcoming article).

Example 3

In reviewing a submission, regulatory authorities should be presented with a comprehensive list of potential product-related and process-related impurities. The source and type of each impurity should be carefully considered (i.e., biological vs. chemical) when assessing its potential impact. Appropriate guidance documents (e.g., ICH Q3[R2]: Impurities in New Drug Substances and ICH Q5A[R2]: Viral Safety Evaluation of Biotechnology Products Derived from Cell Lines of Human or Animal Origin) should be consulted which identify impurities for which specific limits should be implemented. When performing a risk assessment for identified impurities, sponsors may attempt to leverage existing data obtained for similar product types or processes. This approach requires a thorough justification supporting that the products/processes are sufficiently likely to leverage historical data. Similarly, firms that lack robust DI systems may fail to monitor and set appropriate specifications for relevant impurities, leading to negative inspection findings. Having data that is accurate, complete, consistent and available is critical here; reliable, trustworthy data provides knowledge that can give both the submission sponsor and the health authority confidence and contribute to valid decisions.

Conclusion

Despite the tangible benefits of incorporating good KM practices, KM and its importance in manufacturing products of the highest quality is an often overlooked aspect of the pharmaceutical industry. Similarly, the interconnectedness of KM and the way data is managed through governance to ensure its integrity and quality is just beginning to be explored. As the volume of data and information collected for products and processes grows, it becomes even more imperative that these assets are properly collected, stored and shared to facilitate decision-making at key points. The knowledge we acquire and maintain is critical to both firms and health authorities as we make decisions that contribute to improving the health of individuals and our broader communities.

As the pharmaceutical industry continues to change, particularly in terms of third-party (e.g., contract development and manufacturing organizations or CDMOs) and the use of artificial intelligence, we need to consider the relationship of these changes to KM.

References

- International Council for Harmonization. ICH Q10 – Pharmaceutical Quality Systems. 4 June 2008. https://www.ich.org/page/quality-guidelines (accessed 2 Sep 2024).

- Pharmaceutical Inspection Cooperation Scheme. PICS Guidance: Good Practices for Data Management and Integrity in Regulated GMP/GDP Environments. 1 July 2021, https://picscheme.org/docview/4234 (accessed 2 Sep 2024).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Draft Guidance: Data Integrity for In Vivo Bioavailability and Bioequivalence Studies, April 2024. https://www.fda.gov/media/177404/download (accessed 18 Sep 2024).

- IBM. What is knowledge management? Undated, https://www.ibm.com/topics/knowledge-managementb (accessed 2 Sep 2024).

- Brown, J. S. & Duguid, P., The Social Life of Information (Harvard Business School Press, 2000)

- European Commission, EudraLex Volume 4, Annex 1: Manufacture of Sterile Medicinal Products. 22 Aug 2022. https://health.ec.europa.eu/medicinal-products/eudralex/eudralex-volume-4_en (accessed 2 Sep 2024).