Microbial Ingress No Longer an Effective CCI Test Method

In the realm of pharmaceutical sciences, ensuring the integrity of parenteral container closures is paramount to maintaining product sterility and safety.

The methods employed for container–closure integrity (CCI) testing play a crucial role in this process, influencing regulatory compliance and product quality assurance. At its core, CCI testing aims to prevent the ingress of contaminants into pharmaceutical products, particularly in parenteral formats where sterility is non-negotiable. Microbial-ingress testing was a practical mode for evaluating a container’s ability to maintain sterility. The integrity of a closure directly impacts the product's shelf life, efficacy and, overall, patient safety. Historically, the evaluation of sterility and CCI were tightly intertwined, and microbial-ingress testing was the gold standard to establish CCI and product sterility.

With the advent of new drug products, delivery systems and inspection technologies, the microbial-ingress test method has lost scientific relevance for CCI.

The Kirsch Study

The study by Kirsch et al. (1997), often hailed as a benchmark in microbial-ingress testing, underscores the impact of submicron defects on sterility assurance. It demonstrates convincingly that even small defects can compromise the integrity of container closures, potentially leading to microbial ingress under specific conditions. This study was the first and only peer-reviewed article that took up the challenge of answering the question: What is the critical defect size for sterile products? (1)

One of the significant criticisms of microbial-ingress testing lies in its probabilistic nature and the lack of a globally standardized methodology. Unlike deterministic methods that provide clear, pass/fail outcomes based on measurable parameters, microbial-ingress tests can vary significantly depending on testing conditions and interpretations. This variability raises concerns about the consistency and reliability of results across different testing laboratories and scenarios.

Kirsch et al. established several important considerations related to CCI and the microbial ingress test. It established that defects below 1 micron in size can still present a risk for microbial ingress. It also established that the risk of microbial ingress was almost certain as the defect size increased to the 10-micron mark. This microbial-ingress study was always thought to be a gold standard to assess a container’s ability to maintain sterility. Additionally, one of the most profound yet overlooked findings of the Kirsch study were these two simple takeaways:

- Microbial ingress can occur with defects of sizes between 1 and 10 microns.

- Microbial ingress is not able to reliably detect defects of sizes between 1 and 10 microns.

The Kirsch study brought to light the variable method performance. If sterility was a golden standard for sterile products, but the method to establish that characteristic is highly probabilistic, that method itself is not reliable for evaluating CCI. The Kirsch study showed what microbes can achieve and the probabilistic nature of microbial-ingress test results. The microbial-ingress method has provided general clarity around the risk of ingress but does not provide the tools to mitigate that risk.

Despite the general clarity microbial ingress provides around the risk of ingress, the methodology behind creating the test procedure is still unclear. The industry is left without guidance for rigid parenteral products, with the only standardized method relating to single-use systems. ASTM E3251-23 Standard Test Method for Microbial Ingress Testing on Single-Use Systems, which focuses on the methodology used to establish the microbial integrity of a single-use system or to determine the maximum allowable leakage limit, directly focuses on CCI. The standard heavily weighs on arbitrary “Relevant Conditions” to create the parameters and specifications for the method and explicitly states that:

Any size defect may be forced to fail under sufficiently aggressive conditions (including a large enough sample size, high differential pressure, or high hydrostatic pressure, for example) that would not ordinarily reflect normal use conditions (2).

If a method can be forced to fail under certain conditions, it can also be forced to pass. The results of microbial-ingress testing can be influenced by operators and test-method developer bias. Although E3251 can be used for alternative containers, such as rigid parenterals (4.4.4), the limitations and bias remain.

In other life-science spaces, guidance is provided by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), where the agency recommends microbial-ingress testing for Intravascular Administration Sets Premarket Notification Submissions, but no guidance is provided on a standard procedure (3). Some laboratories have taken the lack of industry guidance into their own hands and created elaborate test procedures to challenge new packages after deeming common practices unfit for current sterility and stability requirements (4).

Position

The concept of CCI and microbial ingress were once synonymous. Microbial ingress and sterility testing were the determining measures of CCI. Despite more deterministic CCI methods being developed for industry, there remains a comfort in using physical methods such as microbial ingress. While microbial ingress remains unevolved in the ability to detect defects, technology and regulation have evolved significantly.

The scope of CCI has evolved well beyond the protection of sterility. Parenterals need to be equally evaluated for risk of oxygen, moisture or bacterial ingress to the drug product. Today, CCI stands alone as an evaluation of the container performance, of which acting as a microbial barrier is a performance characteristic.

Since 1997, no further studies beyond Kirsch et al. have addressed the test method’s performance. There is no global standard for microbial-ingress testing for the performance of CCI, nor is there a unified or recommended approach. USP General Chapter <1207> Package Integrity Evaluation—Sterile Products discourages using microbial-ingress methods over deterministic alternatives for establishing CCI (5).

In 2008, the FDA published Guidance for Industry: Container and Closure System Integrity Testing in Lieu of Sterility Testing as a Component of the Stability Protocol for Sterile Products. At that time, only a few technologies existed to support deterministic CCI, and the technical importance of sterility still held regulatory prominence over other environmental contaminants. The 2008 guidance document established a regulatory position in which sterility and CCI are two separate evaluations, sterility focusing only on the sterile nature of the process and not CCI. The guidance document provides the industry with the open pathway to properly address CCI independently of microbial ingress(6).

Path Forward

More than 15 years after the publication of the 2008 guidance document on CCI, the debate on how best to identify and mitigate risks is still vibrant. The concept of holistic CCI has broadened the focus for CCI through space and time to capture container–closure performance for the full life cycle of a product. The technologies and methods available for both CCI and sterility testing have evolved to improve reliability and accuracy. The products and delivery systems are more complex and have varying requirements. One thing that has not evolved is the fundamentals of biology and physics, the factors that would improve the microbial-ingress test method. Test method standards associated with microbial ingress have also not advanced from the position of being little more than a probabilistic biological indicator.

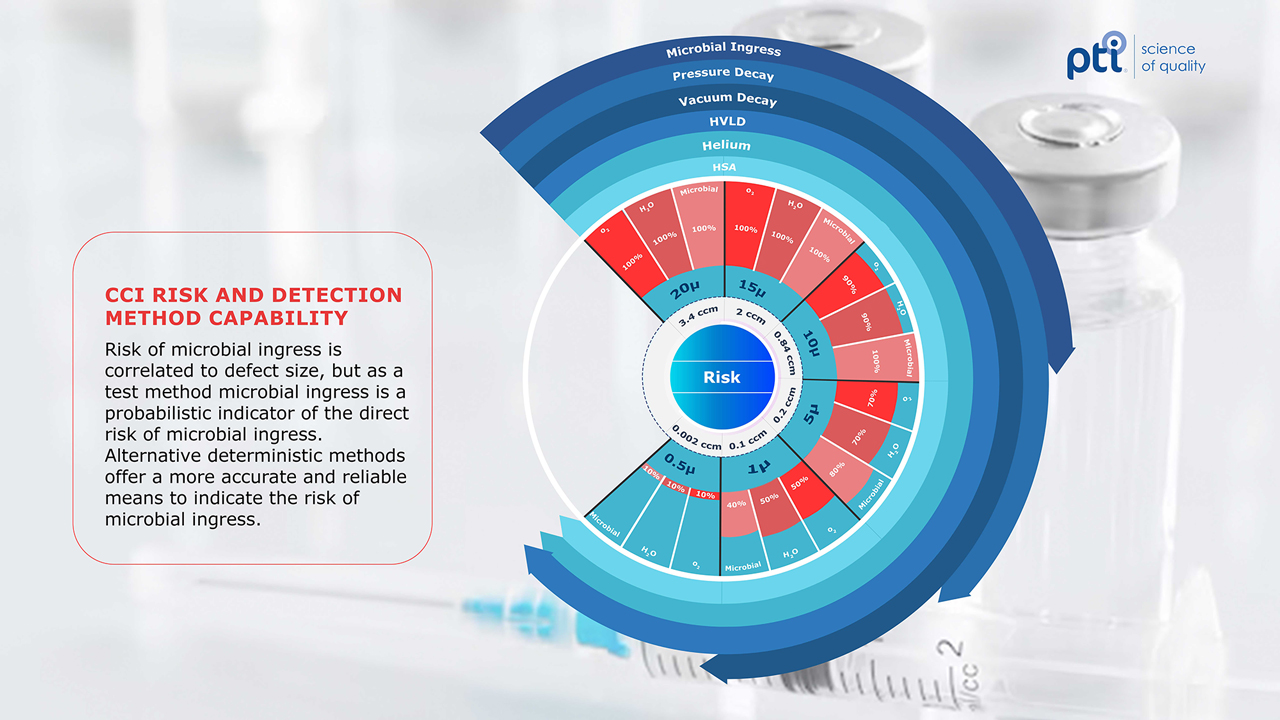

Next-generation CCI solutions are detailed out in USP’s Chapter <1207> Packaging Integrity Evaluation-Sterile Products. The chapter outlines deterministic methods that follow a predictable, controlled process that produces a measurable result. Methods such as vacuum or pressure decay, high voltage leak detection (HVLD), helium leak detection and headspace analysis (HSA) are foundational solutions within the deterministic CCI space. These methods vary in scope and capability. Helium leak detection is highly sensitive to small leaks but requires greater sample preparation. Figure 1 highlights the risk of environmental contaminants and the associated level of leak detection by foundational CCI methods. The other methods mentioned vary in practicality, non-destructive nature, smallest detectable leak size and overall test method speed, among other characteristics. Ultimately, each method applies scientific principles to provide the most accurate and reliable measure of container closure integrity.

There was a time and place when the microbial-ingress method belonged in the conversation of CCI. While the concern for sterility remains part of the CCI discussion, the advent of new technologies that are more capable of CCI has effectively replaced microbial ingress. The conversation on CCI was once encompassed within the evaluation of microbial-ingress testing.

As with all pharmaceutical risk management, mitigating risk begins with fully understanding the risk. CCI is an interdisciplinary and dynamic space. Each application will present different risks, challenges and opportunities. From a regulatory standpoint, deterministic CCI test methods are gaining favor due to their robustness and ability to promptly provide actionable data.

Regulatory bodies recognize the limitations of microbial-ingress testing and increasingly emphasize the importance of deterministic testing approaches that align with current good manufacturing practices and international standards. This shift reflects a broader industry acknowledgment of the limitations of probabilistic tests in ensuring consistent product quality and safety.

Summary

The industry has developed a wide variety of deterministic test methods that evaluate CCI with greater accuracy and sensitivity than ever before. Today's test methods available in the marketplace can capture defects in the microbial-ingress range with much greater reliability and accuracy. Provided the context of the microbial-ingress performance and CCI technology capability, it is difficult to argue any future for the microbial-ingress test method.

In contrast, deterministic CCI Test methods offer a more reliable and standardized approach to assessing container closure integrity. These methods, which include technologies such as Microcurrent high-voltage leak detection (HVLD), vacuum decay, and laser-based headspace analysis, provide quantitative data that directly correlate with the absence of leaks above a defined threshold. Such deterministic outcomes are crucial for regulatory compliance and provide pharmaceutical manufacturers with clear indications of product safety and quality.

In conclusion, while microbial ingress testing has historically served as a benchmark for container–closure integrity assessment, its probabilistic nature and lack of standardization present significant challenges. Deterministic CCI test methods offer a compelling alternative, providing pharmaceutical scientists and manufacturers with reliable, consistent and actionable data to safeguard product integrity. As the industry continues to evolve, embracing deterministic testing approaches promises to enhance regulatory compliance, streamline quality assurance processes, and, ultimately, bolster patient safety in the realm of parenteral packaging.

References

- L. E. Kirsch, L. Nguyen, C. S. Moeckly and R. Gerth “Pharmaceutical Container/Closure Integrity. II: The Relationship between Microbial Ingress and Helium Leak Rates in Rubber-Stoppered Glass Vials,” PDA J Pharm Sci Technol 51, no. 5 (1997): 195-202. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9357305/.

- ASTM International, “ASTM E3251-23 Standard Test Method for Microbial Ingress Testing on Single-Use Systems,” Aug 11, 2023. https://www.astm.org/e3251-23.html.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration, “Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff: Intravascular Administration Sets Premarket Notification Submissions [510(k)],” Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Jul 11, 2008. https://www.fda.gov/media/71046/download.

- Degenhard Marx, Thorsten Bartsch, Reinhold Wohnhas, and Walter Zwisler, “Microbial Integrity Test for Preservative-Free Multidose Eyedroppers or Nasal Spray Pumps,” Pharm Ind 81, no. 9 (2019): 1247-1252. https://aptar.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Overview-of-microbial-integrity-tests-for-preservative-free-nasal-spray-pumps-and-multidose-eyedroppers.pdf.

- U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention, “General Chapter <1207> Package Integrity Evaluation—Sterile Products,” in the Pharmacopeial Forum, Vol. No. PF 40(5), 01-Aug-2016. https://www.usp.org.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration, “Guidance for Industry: Container and Closure System Integrity Testing in Lieu of Sterility Testing as a Component of the Stability Protocol for Sterile Products,” Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, February 2008. https://www.fda.gov/media/76338/download.