Points to Consider When Applying QRM Principles to Better Manage the Partnership/Relationship with Contract Operations

For those who may have missed the opportunity to attend the PDA/FDA Joint Regulatory Conference 2024, this article provides a summary of my presentation, “Applying QRM Principles to Navigate Better Outcomes and Partnerships with Your CMO.”

I should begin with a public service announcement (PSA) to emphasize why effective quality risk management (QRM) is not just beneficial but a regulatory expectation. This will be followed by points to consider when applying QRM principles to dynamic situations representing partnerships and relationships with contract development and manufacturing organizations (CDMO) and suppliers.

PSA: QRM Is Not a Choice…It Is the Law

Most of us remember the changes that were introduced as part of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA) that amended the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) in 2012 (1). FDASIA included several monumental changes that had an immediate and direct impact on both the FDA and the global pharmaceutical industry, such as the establishment of the Generic Drug User Fee Act and the Mutual Recognition Agreement. There were several other changes that did not generate the same level of attention, and I suggest that there may be certain changes that have been conveniently overlooked or relegated.

Section 711 of FDASIA amends the definition of the current good manufacturing practice (CGMP) regulations provided in Section 501(a)(2)(B) of the FD&C Act, introducing the words “oversight” and “managing the risk” to the definition.

SEC. 711. Enhancing the safety and quality of the drug supply.

Section 501 (21 U.S.C. 351) is amended by adding the following flush text:

For purposes of paragraph (a)(2)(B), the term current good manufacturing practice includes the implementation of oversight and controls over the manufacture of drugs to ensure quality, including managing the risk of and establishing the safety of raw materials, materials used in the manufacturing of drugs and finished drug products.

The addition of these two concepts into the definition of CGMP would have a profound impact on what it means to be “in compliance with the CGMP.” It has been more than 10 years since this change was enacted, but it appears that many pharmaceutical companies failed to understand the message. In short, if you are not implementing effective oversight or are not effectively managing the risk(s), then your operation is technically in violation of the CGMP. This is why QRM has been such a hot topic for the last decade. However, there is evidence to suggest that we must do better.

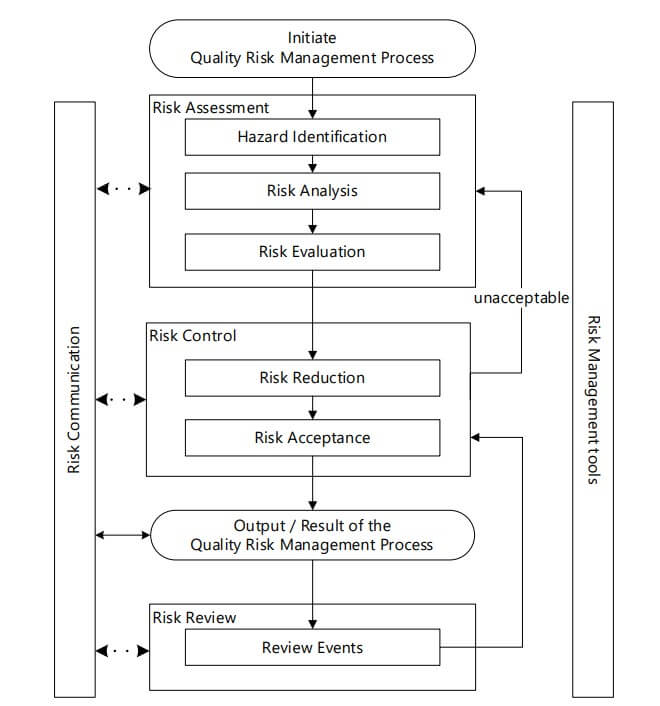

It should be clear that maintaining oversight and managing risk are connected, and we could have a separate discussion that focused on how to implement effective oversight. But, for this discussion, we will focus on points to consider for effective QRM and frame the discussion around the complications that are inherent to the dynamics of contract operations. Most of us understand that the primary resource for QRM principles is the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Quality Guideline Q9(R1): Quality Risk Management, which was recently revised (2); see Figure 1 for ICH’s updated flow chart. However, the basic principles remain the same, and for the purpose of this discussion, we will focus on the evaluation of risk.

It is important for all of us to understand that you cannot effectively manage the risk if you are unaware of the risk or choose to ignore it. Some may be confused by the idea of ignoring the risk, but I suggest that there is a continual stream of evidence indicating that poor decisions lead to unfavorable outcomes. Each time I review an FDA Warning Letter, I recognize that each violation represents the failure to effectively manage the risk. I cannot help but wonder how many internal audits, customer audits or regulatory inspections were conducted at the site that received this enforcement. How did the existing quality management system (QMS) allow for the failure to communicate and manage the risk effectively? Were there provisions in the quality agreement establishing the responsibilities and process for communicating the risk? Was the source of each violation something that surprised the management at the site, or was it an ongoing issue that was mismanaged and eventually resulted in a documented violation?

We all need to recognize this pattern and take action to reduce the likelihood of recurrence. This pattern of ignoring the risk is a function of weakness in the management review process. In my experience, there can be a push to have everything in the dashboard identified as green (as opposed to yellow or red). If there is an effort to sugarcoat the updates or the management prefers to view everything through rose-colored glasses, then that organization can expect to encounter issues with the effective management of risk. Do not let this happen at your company!

The Dynamics: The CDMO, the Supplier and the Sponsor

The requirements for effectively managing the risk are the same for the CDMO, the supplier and the sponsor, but the dynamics are different. The supplier establishes the internal standards for compliance with the CGMP and provides products to several different customers. The CDMO establishes the internal standard for compliance with the CGMP and provides services tailored to meet each specific customer's needs. The sponsor must monitor compliance with CGMP and allow the supplier and CDMO to complete the tasks within their respective operations. In each of these situations, there are obstacles to effectively manage the risk. Most of us may assume that most of the risk is generated within the contract operations. However, the CDMO may encounter an additional "regulatory risk" when the customer proposes a plan that conflicts with the internal standards at the CDMO or, even worse, violates the CGMP. Ultimately, the CDMO would be directly responsible for addressing any concerns during a regulatory inspection. There is a long history that includes this theme, and there are direct connections with the continual evidence provided by many of the recent violative inspections and enforcement actions published by the FDA.

The parties on both sides of the conference table should take a moment to consider how quality agreements and audit programs (both internal and external) have been utilized in the past and how these tools can be a component of an effective continual improvement program.

Quality Agreements: Frame the Partnership, Facilitate the Relationship

When the FDA published the Guidance for Industry: Contract Manufacturing Arrangements for Drugs: Quality Agreements, it was the first step in ensuring a successful quality agreement (3). It has been nearly a decade since this guidance was published, and obstacles to successful implementation remain. In most cases, quality agreements are generic and lack specificity, especially regarding assigning the responsibilities related to the QMS. It will also be important to recognize that you may not get it right the first time, and there should be provisions for a routine review and evaluation to determine if revisions can better facilitate the process. Meanwhile, circling back to the discussion about the conflicts between sponsors and CDMOs, how does the quality agreement address considerations for establishing and monitoring critical process parameters? Is the CDMO required to accept the protocol from the Sponsor without discussion? How have the provisions of the quality agreement been developed to provide a favorable outcome for both parties?

I suggest the quality agreement establishes the “partnership” between the parties. The manner in which the provisions are implemented and the day-to-day interactions are what create the “relationship.” It should be understood that the partnership and the relationship are critical to maintaining a successful contract operation.

Quality Agreements

- Ensure that the QMS responsibilities are well-defined

- Establish a timeframe for routine review, evaluation and revision

- Develop mechanisms for conflict resolution

- Provide the opportunity to develop the relationship as well as the partnership

Audit Programs: Are They Just a Ceremony?

As I continue to reference the stream of evidence with each violative inspection and published enforcement action, it should be clear to each reader that the current audit methods are not producing the desired results. If you are convinced that the goal of the audit program is to evaluate compliance with CGMP, then it will be important for everyone to remember that the regulations cited in the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations provide for the “minimal standard.” This means that a pharmaceutical company should do nothing less than what is instructed in the regulations. Compliance with CGMP is just the foundation that should be used to build a robust quality management system that has the tools to understand, evaluate and manage the risk effectively. The audit programs are essential tools for this critical mission.

First, everyone should be aware that if a company relies solely on the results of the last regulatory inspection to determine the compliance status at a given supplier or CDMO, this is a recipe for unidentified risks that create obstacles to success. Any inspection or audit is only a snapshot of the operations during the visit. It will require a boots-on-the-ground operation at each supplier or CDMO to effectively evaluate the risk. It will take a continual effort to establish a risk-based approach for an effective audit program. There should be no confusion that spending a few days on-site, reading standard operating procedures, is nothing more than a ceremony, and there should be a plan to effectively utilize the limited time that is provided for customer audits. The plan should include using an audit team where each member has the background and experience necessary for an effective audit.

The background and experience of each member of the audit team are especially important when evaluating the risk associated with a data integrity/data governance program. We have been managing the risk associated with an evolving regulatory expectation related to data governance for over 10 years. This started when we accepted data that had been generated in systems before there were stringent controls. Then, as the risk assessments began to dictate primary and secondary improvements (investments), managing the risk related to those secondary systems was difficult, which involved procedures for specific oversight and additional controls until the next set of improvements was implemented. Finally, we have come to the most recent situations, where we need only confirm the electronic controls for data generation and storage and rely on the procedures and documentation for oversight and data review. However, the evaluation of risk related to data governance will continue to demand flexibility and adaptation as the concepts are implemented for systems in the production equipment, and we should not overlook the challenges associated with manually recorded data in batch production records and other documents.

What about the internal audits at your supplier or CDMO? Does your audit program include an evaluation of the effectiveness of the internal audits at your contract operation? Is that internal audit just a ceremony? Most of us are aware that there are complications related to internal audits, specifically, the difficulty of being objective when you are in your own house. Evaluating the effectiveness of the internal audit program is essential for supporting the QRM at that supplier or CDMO. The results of that internal audit can be your first line of defense for recognizing and managing the risk of that contract operation.

Building Better Audits

Developing the mechanisms to understand, evaluate and manage risk can be difficult. When you introduce the idea of managing risk through a contract operation, it only increases the difficulty. An effective audit program is certainly an essential component to managing the risk at your supplier or CDMO effectively. This leads back to my previous statements about the continual stream of violative inspections and enforcement actions. This evidence suggests that what we have been doing is not working. If there was an easy solution to this issue, it probably would have been presented by now, so it appears that more effort will be necessary.

Additionally, there are complications to the audit process from both sides of the table and considerations for fostering a productive relationship between the auditee and the auditor. As the auditee, the main issue may be the burden of hosting audits throughout the calendar year, with more requests than available dates for audits. Every customer will request an audit, per the quality agreement, but it will not be possible to grant every request. This issue has forced most contract operations to limit the number of days for the on-site audit. What can you accomplish during a two-day audit evaluating aseptic processing operations at your CDMO? It is extremely likely that this would be an obstacle to effective QRM at this CDMO. In this case, the auditor must develop a risk-based and directed approach for the focus of the audit.

The quality of the input presented during an external audit is also a major complication for the auditee. Most auditees will state that the external audit is an opportunity for a “second set of eyes” to review and evaluate the operations. What if that input is nonsense? What if that input is in no way value-added? I routinely encounter issues during audits, and the source of the confusion often comes from input during a customer audit. Is the customer always right? It will be critical for the auditee to develop a mechanism to filter through the “nonsense” and ensure that all changes are based on value-added input. Following this same concept, the auditor should try to keep the nonsense to a minimum. The results of the audit should not be clouded by the ego or opinions of the auditor. The audit observations should be grounded in the applicable regulations and presented as soon as they are recognized. There is no value in waiting to bring a surprise observation at the closeout meeting. How the audits are conducted is a critical component for fostering a collaborative relationship between the auditee and the auditor.

Auditor: Ensure that the observations and input are grounded in the applicable regulations (no nonsense or opinions)

Auditee: Develop mechanisms to filter the input to recognize the value-added content (filter the input)

Conclusion

There are no easy answers to the questions and concerns surrounding the methods for effective QRM at a supplier or CDMO. As the pattern continues for the pharmaceutical industry to outsource critical operations, these questions and concerns will be amplified. The evidence that effective QRM continues to elude many in the pharmaceutical industry is published routinely. Each of us should agree that more effort will be necessary. With special considerations for establishing the partnership and fostering the relationship through the quality agreement and a focused, risk-based approach to the external audit, there may be opportunities to navigate a better outcome with your Supplier or CDMO.

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA), July 2012.

- International Council for Harmonisation. Quality Guideline Q9(R1): Quality Risk Management, July 2023.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance For Industry: Contract Manufacturing Arrangements for Drugs: Quality Agreements, November 2016.