Thanks, Science!

The closing plenary session of the 2021 PDA/FDA Joint Regulatory Conference, “Thanks Science,” examined the strides science and technology have made to improve public health, even though the public has seemingly become less trusting of scientists.

In his presentation, “Vaccine Diplomacy in a Time of Anti-Science,” Peter Hotez, MD, PhD, shared his long history of advocating the benefits of vaccinations, particularly for children. As the Dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Hotez has mostly been involved with the development of vaccines for parasitic diseases throughout his career and has been working with coronaviruses over the last 10 years. He is also head of the Texas Children’s Center for Vaccine Development. These groups have made enormous strides in vaccinating the world’s children and reducing the number of deaths of children under the age of five, with the help of the U.S. FDA, the Gavi Alliance and other global health organizations.

Hotez points to many drivers behind the formation of new hot zones of preventable disease globally, including political instability, climate change, urbanization, deforestation, and the very aggressive rise in anti-science.

Hotez appealed for more international help to effect technology transfer of COVID vaccines to lower middle-income countries. “Vaccine Diplomacy” is an effort to counter these drivers by gaining international cooperation to develop vaccines and expanding access to vaccinations globally. Whether it be new vaccine technology or traditional, the focus is on meeting the needs of individual countries.

For over two decades, Hotez has used good science to improve communications about the benefits and safety of MMR vaccines to “combat” misinformation, particularly the unfounded belief they cause autism.

Each time antivaccine voices have “moved the goal posts,” the scientific community has responded with evidence against it. Today, Hotez sees the politicization of antivaccination viewpoints with calls for “health freedom,” which is causing new outbreaks of measles and propagating the anti-COVID-19 vax and mask movement.

Gene Therapy Treats Rare Spinal Disease

In recent years, gene therapy has become more of a reality, according to Peter W. Marks, MD, PhD, Director of CBER, U.S. FDA, during his presentation “Bringing Bespoke Therapeutics into Being.”

Marks shared the remarkable results of the Onasemnogene clinical trial, a drug that treats patients with infantile onset spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). While most SMA patients die before the age of two, 14 of the 15 trial patients are now in the normal range. To emphasize the power of this therapy, Marks showed an image of a three-year-old patient, Evelyn, running around and playing; “Something never seen in untreated children,” he commented.

Gene therapy, Marks said, could be used to address hundreds of other disorders that affect thousands of people, and edited molecular defects could possibly relegate common diseases to the level of very rare diseases.

Personalized medicine is transitioning to individualized medicines, and the FDA is very interested in facilitating created products as a way to see more gene therapies come about.

To help distinguish among the various kinds of gene therapies, Marks compared them to men’s suits: personalized meds are “ready-to-wear/off the rack,” customized therapies are “made-to-measure that can be fitted,” and bespoke therapies are customized suits created for the individual.

In a hypothetical example, he theorized about how the challenges of creating individualized medicine might be overcome in the future:

- Manufacturing—An automated device that could perform large parts of processing to surmount the costs of producing only a few doses of medicines for rare disorders

- Nonclinical Development—Use of such new model systems as organoids and humanized mice to facilitate safety testing

- Clinical Development—Creating templates for collecting baseline and historical data and Bayesian clinical trial designs to help determine efficacy in small populations

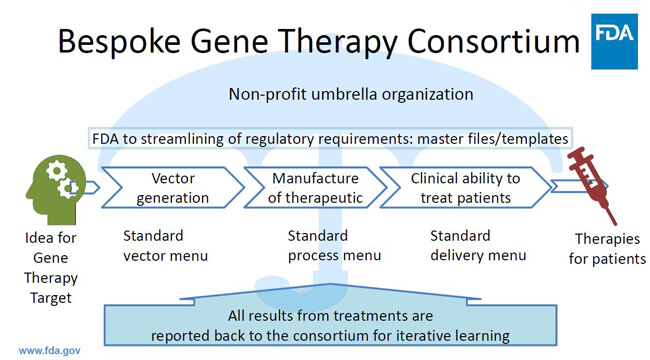

- Product Access—Public-private partnerships could enable product access in diverse populations and create a system where manufacturers could envision this working (see Figure 1)

Figure 1 Concept of public-private partnership enabling product access to diverse populations

Figure 1 Concept of public-private partnership enabling product access to diverse populations

One concept in development FDA is looking into is making a “cookbook” for the development and manufacturing of bespoke therapeutics, so one vector of a product could be changed without changing the entire product. Standardization among academic institutions would make it easier to transfer technologies to commercial manufacturing, he said, and regulatory aspects would need to be developed to leverage nonclinical and manufacturing data from one application to another. In this and other ways, FDA is committed to advancing the development of cell and gene therapies for all populations.

Transparency, Information and Misinformation

The two speakers fielded numerous questions during a rousing Q&A session on the approval of COVID-19 vaccines, regulatory transparency and communication of information. Did transparency in regulatory decision-making help or hurt initiatives to increase vaccination? What can FDA and industry do to expose and prevent misinformation from being perpetuated on social media? What can we do to counteract misinformation and support public messaging on science and product quality?

FDA’s Peter Marks said the Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) for COVID-19 vaccines were held to as high a standard as possible—not a BLA (Biologics License Application) in name, but in substance—and FDA was confident the products it approved to address the pandemic were of good quality.

“Transparency is very important,” he said. “It’s important that people understand here that there is no magic.” The public is hearing the truth, but cutting-edge science can be confusing, so it is important to “minimize the noise” in the messaging.

Hotez suggested if there was a “silver lining” in the pandemic, it was that people got used to hearing from scientists and scientist physicians in “a very granular way and in a lot of detail.”

People are willing to tolerate a level of complexity in the message if their lives depend on it. He believes that, in the future, scientists and physicians have a responsibility to learn how to communicate to the public and have that training built into their graduate and doctorate studies. He said the “antivax” groups exploited opportunities when there were disagreements among officials and used it to create a great divide among the American people.

Marks said FDA tried to provide accurate, accessible information, but found itself combating the proliferation of misinformation, especially through social media. As an example, he noted FDA had to advise the public to refrain from using dog deworming to fight the virus. What he found most troubling was that there was often monetary gain behind the distorted messages.

Hotez commented that “social media is a minefield.” He is active on Twitter and uses it to provide accurate information, but also as teachable moments to counter misinformation. If he can identify two or three sources of what he calls the “anti-science aggression,” he strives to clarify from where the message is originating and how it is used incorrectly to influence others. Anti-science aggressionists are no longer grassroots movements, he said, they are now an empire.

Marks also pointed out the increase of anti-science forces that use “pseudo-science” to promote their message. “It’s very, very scary,” he said, “because you actually have things appear in what looks like journals—or some do make it into journals—and that makes it look credible.”

Moderator for the session, Mary E. Farbman, PhD, Executive Director of Global Quality Compliance at Merck & Co. and member of the planning committee, then asked: As industry professionals and scientists in the audience, do you recommend we engage with these contrarian scientists or is it best to ignore them, not give them a platform?

Hotez’s said he tries to “avoid going down the rabbit hole of getting into a Twitter fight.”

Instead, if someone makes an obviously flawed point, he believes finding a paper to refute it, making it public and explaining why it’s flawed is a more effective means of communication. Marks reiterated the importance of providing accurate information in clear communications without overwhelming.

“It’s okay to acknowledge uncertainty,” he said. “People are more able to understand the science, but we have to keep it in plain English…explaining how the benefits outweigh the risks.”

Peter Hotez, MD, PhD, is a professor of pediatrics and molecular virology at Baylor College of Medicine, where he also co-directs the Texas Children’s Center for Vaccine Development as an Endowed Chair in Tropical Pediatrics. Hotez obtained his undergraduate degree from Yale University and his MD and PhD from Weil Cornell Medical College and Rockefeller University. A vaccine scientist who has led the development of vaccines to prevent and treat neglected tropical diseases and coronavirus infections, he has authored four books and more than 550 scientific articles promoting global health, vaccines and immunizations. Hotez is also a vocal proponent countering antivaccine and anti-science movements.

Peter Hotez, MD, PhD, is a professor of pediatrics and molecular virology at Baylor College of Medicine, where he also co-directs the Texas Children’s Center for Vaccine Development as an Endowed Chair in Tropical Pediatrics. Hotez obtained his undergraduate degree from Yale University and his MD and PhD from Weil Cornell Medical College and Rockefeller University. A vaccine scientist who has led the development of vaccines to prevent and treat neglected tropical diseases and coronavirus infections, he has authored four books and more than 550 scientific articles promoting global health, vaccines and immunizations. Hotez is also a vocal proponent countering antivaccine and anti-science movements.  Peter W. Marks, MD, PhD, was named Director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in January 2016 after serving as the Center’s Deputy Director for four years. The center is responsible for assuring the safety and effectiveness of biological products, including vaccines, allergenic products, blood and blood products, and cellular, tissue, and gene therapies. Marks received his graduate degree in cell and molecular biology and his medical degree at New York University and completed Internal Medicine residency and Hematology/Medical Oncology training at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He has worked in academic settings teaching and caring for patients and in industry performing clinical development of hematology and oncology products.

Peter W. Marks, MD, PhD, was named Director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in January 2016 after serving as the Center’s Deputy Director for four years. The center is responsible for assuring the safety and effectiveness of biological products, including vaccines, allergenic products, blood and blood products, and cellular, tissue, and gene therapies. Marks received his graduate degree in cell and molecular biology and his medical degree at New York University and completed Internal Medicine residency and Hematology/Medical Oncology training at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He has worked in academic settings teaching and caring for patients and in industry performing clinical development of hematology and oncology products. Mary E. Farbman, PhD, as Executive Director of Global Quality Compliance at Merck & Co., Inc., leads a team of GMP experts responsible for compliance support at Merck’s manufacturing facilities around the globe. She previously worked at FDA CDER’s Office of Compliance authoring and reviewing warning letters and compliance documents, conducting microbiological reviews of therapeutic protein manufacturing processes, and performing pre-license inspections of BLA products. In industry, Farbman has worked in various compliance and auditing roles at both the site and global levels as well as in the R&D arena. Her areas of expertise include biotechnology, sterile products, and analytical techniques.

Mary E. Farbman, PhD, as Executive Director of Global Quality Compliance at Merck & Co., Inc., leads a team of GMP experts responsible for compliance support at Merck’s manufacturing facilities around the globe. She previously worked at FDA CDER’s Office of Compliance authoring and reviewing warning letters and compliance documents, conducting microbiological reviews of therapeutic protein manufacturing processes, and performing pre-license inspections of BLA products. In industry, Farbman has worked in various compliance and auditing roles at both the site and global levels as well as in the R&D arena. Her areas of expertise include biotechnology, sterile products, and analytical techniques.