The Production of Suitable Inoculums for Microbial Tests

Given the importance of inoculums (perhaps more correctly, inocula) to the quantitative promotion of microbiological growth in media, antimicrobial effectiveness testing of multiple-use drug products, and in-use microbiological stability testing of injectable products, it is surprising how little attention is given to the fundamentals of inoculum preparation.

This issue was the subject of a largely forgotten book on the relevance and reproducibility of inoculums that highlighted that inoculum preparation was a source of inconsistent results in Antimicrobial Effectiveness Testing. The author discusses the issues he believes are pertinent to this topic (1).

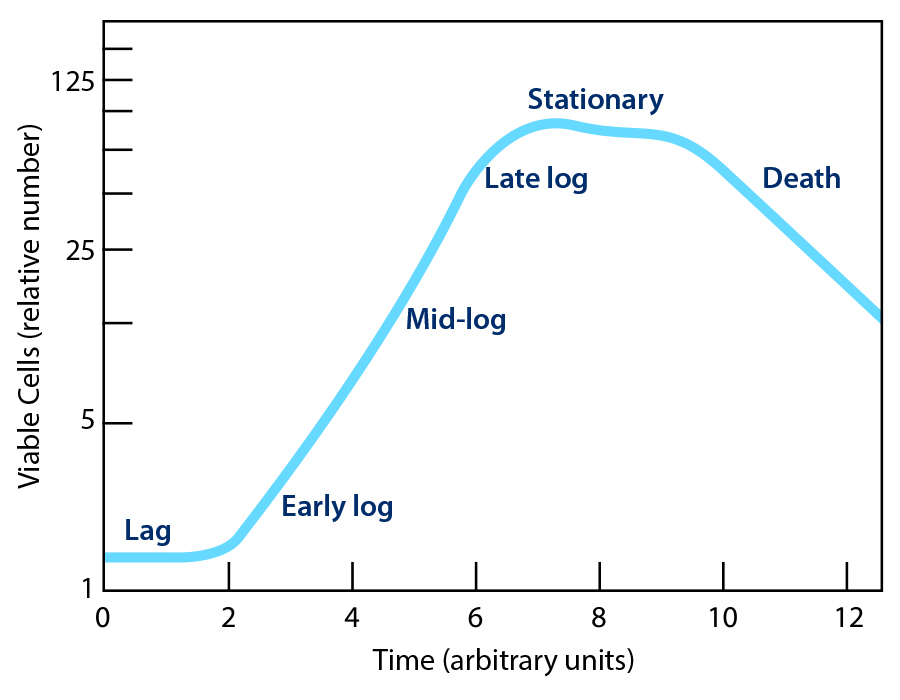

Microbial Growth Phases

The classical description of the growth phases of a microbial culture is divided into four phases: lag, log, stationary, and death (Figure 1). These distinct phases are apparent when cell counts, or optical density are plotted against incubation time. An understanding of these phases is necessary to produce suitable inoculums, which are briefly discussed.

Lag Phase

The lag phase is the initial period where bacteria and yeast are metabolically active but not yet dividing, as they adapt to a new environment, such as fresh microbiological culture media or a test material, by synthesizing enzymes, mRNA, ATP, and metabolites needed for growth and repairing damaged cells, especially the cell membrane. This adaptation phase is dynamic and prepares the cells for rapid cell division in the subsequent exponential (log) phase. The cells in the lag phase may increase in size but do not divide. The duration of the lag phase is influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, potential inhibitors, and nutrient availability, as well as the condition of the microbial cells themselves.

Exponential (Log) Phase

Rapid, often synchronized, cell division occurs in the log phase, with the microbial population doubling at a generation time as short as 20 minutes in rapidly growing bacteria such as E. coli when readily metabolizable substrates, minerals, and growth factors are available in the medium. It is often convenient to subdivide the log phase into early, mid, and late phases, with the mid phase yielding the most homogeneous bacterial cells.

Stationary Phase and Death

When the substrate becomes exhausted and metabolic end-products accumulate, active growth will slow, with the number of cells dying matching those dividing and then stopping. The microbial population will then decline as cells may die or form metabolic-inactive states, including dormant (persister) cells or form resistant endospores

Preparation of Suitable Inoculums for Microbial Test

The culture methods used to obtain sufficient microbial cells for inoculum preparation will determine cell homogeneity and the time to transition from the lag to the log phase of growth when inoculated into fresh microbiological growth media or the test material. The cultures may be grown on solid or liquid media. Colonies steaked onto a plate will differ in density due to dilution, and as they grow in both the vertical and lateral directions, will exhibit a spatiotemporal heterogeneity with the oldest cells in the center and the youngest cells at the edges of the colony. The homogeneity of the cells in an inoculum will be somewhat determined by the steaking technique and the colony selection by the analyst. Genetically identical microorganisms will show cell differentiation within a colony. For example, Bacillus subtilis colonies may contain dormant cells in the center, matrix-producing cells throughout the colony, and metabolically active, motile cells at the growing edges (Tasaki et al, 2017) (2).

Cultures grown in liquid culture may lack the physical restraints of those grown on solid culture. However, they may grow forming clumps of daughter cells or have limited access to nutrients and oxygen when grown in stationary culture. For example, Pseudomonas aeruginosa grows as a surface pellicle in tryptic soy broth in stationary culture. These constraints make the incubation of a liquid culture in a rotary (orbital) shaker incubator to control broth temperature and aeration necessary.

Ideally, a single colony should be inoculated into 2–10 ml of broth and incubated for approximately 8 hours (to enter the

logarithmic phase) to produce a starter culture. It is recommended to use a vessel with a volume of at least four times greater than the volume of the medium. The starter culture should then be diluted 1/500 to 1/1000 into a larger volume of selective

medium and grown with vigorous shaking (around 300 rpm) to mid-log phase (12–16 hours). It may be convenient to grow the starter culture during the day and the larger culture overnight for harvesting the following morning.

Ideally, a single colony should be inoculated into 2–10 ml of broth and incubated for approximately 8 hours (to enter the

logarithmic phase) to produce a starter culture. It is recommended to use a vessel with a volume of at least four times greater than the volume of the medium. The starter culture should then be diluted 1/500 to 1/1000 into a larger volume of selective

medium and grown with vigorous shaking (around 300 rpm) to mid-log phase (12–16 hours). It may be convenient to grow the starter culture during the day and the larger culture overnight for harvesting the following morning.

The selection of the medium and incubation conditions may be important in determining the size of the challenge organism used for sterile filtration validation. For example, the bacterium Brevundimonas diminuta is grown in Saline Lactose Broth in a shaking incubator to achieve a more uniform coccobacillus of about 0.2 microns in size to challenge a sterilizing-grade filter when diluted into the product.

The preparation of inoculums from bacterial endospores requires special attention and is not well performed in Pharmaceutical QC Microbiology Laboratories. What follows is a summary of instructions for preparing a spore suspension from an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Standard Operating Procedure (3).

Use growth from a stock culture tube to inoculate 10 mL tubes of Nutrient Broth and incubate tubes on an orbital shaker for 24 hours at approximately 150 rpm at 37ºC. Use this culture to inoculate manganese-amended Nutrient Agar plates (Nutrient agar containing 5 µg/mL MnSO4·H2O). Inoculate each plate with 500 µL of broth culture, then spread the inoculum with a sterile bent glass rod or a suitable spreading device. Wrap each plate in parafilm or place it in a plastic bag. Incubate plates inverted for 12-14 days at 37ºC.

Following incubation, harvest the spores by adding 10 mL chilled sterile water to each plate. Using a spreader (e.g., a bent glass rod), remove growth from the plates, then pipette the suspensions into tubes containing sterile water. Centrifuge tubes at 5,000 rpm (4,500×g) for approximately 10 minutes at room temperature. Remove and discard supernatant. Resuspend the pellet in each tube with 10 mL of cold, sterile water, and centrifuge at 5,000 rpm (4,500×g) for approximately 10 minutes.

Remove and discard supernatant. Repeat twice. Resuspend the pellet in each tube with 10 mL sterile water. Store the spore suspension at 2-8ºC.

Examine the spore suspension with a phase-contrast microscope or by staining to assess its quality. Examine a minimum of five fields and determine the ratio of spores to vegetative cells (or sporangia). The percentage of spores versus vegetative cells should be at least 95%. Spore suspension from multiple plates can be combined and re-aliquoted into tubes for uniformity.

Details on fungal spore suspension preparation can be found in United States Pharmacopeia <61> Microbiological Examination of Non-Sterile Products – Microbial Enumeration Tests.

Harvesting, Washing and Resuspending the Inoculum

Next, the cells are harvested by centrifugation, then washed, recentrifuged and resuspended in appropriate sterile suspending fluid. The g-force used for centrifugation will depend on the species of the microbial cells. Washing is critical to remove residual nutrients that may influence the recovery of the challenge organisms especially in terms of shortening the duration of the lag phase or reducing the inhibition of antimicrobial agents. The suspending fluid should not contain nutrients like peptone broth. Phosphate buffered saline may be a suitable choice. These considerations are important as the acceptance criteria may be at the analytical variability of a plate count of not greater than 0.5 log increase so small differences in inoculum may be the difference between passing or failing the antimicrobial effectiveness or In-use stability tests.

Homogeneity and Precision of the Inoculum

Ideally a standardized microbial inoculum should consist of a precise count of cells of the same phenotypic status. The author believes that cell grown in a shaken liquid culture harvest at mid log phase will best achieve this. The inhouse prepared or commercially purchased inoculums should be standardized and have storage conditions and expiration dating justified by stability studies. A technology that is highly suitable for determination of cell viability and counting the dispensed cells into a container is cell sorting.

Possible Effects of Cell Heterogenicity on Different Emerging Microbiological Technologies

Depending on the targeted signal of the microbial test method, cell heterogeneity in terms of overall metabolic activity, mRNA turnover, cell division, cell wall integrity and functionality, and cellular composition may affect the analysis. For example, the growth phase may affect the genome number, mRNA level, enzymic activity, ATP content, and amount of storage materials within a cell. The effect of growth phase on these attributes is largely undefined. A recent article demonstrated slight differences in mass/charge ratios across the three-dimensional structure of P. aeruginosa colonies using mass spectrometry imaging (Rosado-Rosa and Sweedler, 2025) (4).

Certification of Primary Standard Cultures

With emerging new microbiological technologies to detect and enumerate microbial cells with signals other than the colony-forming unit (CFU) derived from plate counts, there is need for certified primary standards based on other signals. These may include standards for vital staining, biofluorescence, Coulter counting (impedance), rRNA base sequences, genome count, metagenomic next-generation sequencing (NGS), intrinsic biofluorescence, and ATP content. A NIST-sponsored industry collaboration is working on the development of these standards, emphasizing NGS with the participation of companies marketing commercially prepared inoculums.

Conclusion

Pharmaceutical microbiologists are facing the regulatory imposition of microbial tests that may match or even exceed their analytical capability, resulting in greater challenges to the development of microbiological standards and inoculums. In addition, current standards based on the CFU are proving inadequate for modern microbiological methods based on other signals and must be repositioned using additional parameters for their characterization. In conclusion, more attention must be given to the preparation of low-level inoculums for growth promotion testing and microbial challenge tests to provide standardized, consistent results in line with the low-precision analytical capabilities of the tests.

References

- Brown, M. R. W., & Gilbert, P. (1995). Microbiological quality assurance: A guide towards relevance and reproducibility. CRC Press.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2021, March). Standard operating procedure for the AOAC sporicidal activity of disinfectants test (MB-15-05). https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-12/mb-15-05.pdf

- Rosado-Rosa, J. M., & Sweedler, J. W. (2025). Bacterial biofilm sample preparation for spatial metabolomics. Analyst, 150, 3257–3268.

- Tasaki, S., Nakayama, M., & Shoji, W. (2017). Morphologies of Bacillus subtilis communities responding to environmental variation. Development, Growth & Differentiation, 59, 369–378